Lee, Tay, Balakrishnan, Yeo, and Samarasekera: Mobile learning in clinical settings: unveiling the paradox

Abstract

Purpose

The use of mobile devices among medical students and residents to access online material in real-time has become more prevalent. Most literature focused on the technical/functional aspects of mobile use. This study, on the other hands, explored students, doctors and patients’ preferences and reasons towards the use of mobile devices in clinical settings underpinned by the Technology Acceptance Model 2 (TAM 2).

Methods

This research employs an exploratory research design using survey and semi-structured interviews. An online survey was administered to clinical year medical students, followed by semi-structured interviews with the doctors and patients. Questions for the online survey and semi-structured interviews were derived from previous literature and was then reviewed by authors and an expert panel. A convenience sampling was used to invite voluntary participants.

Results

Survey findings showed that most medical students used their devices to find drug information and practice guidelines. The majority of the students accessed UpToDate followed by Google to access medical resources. Key barriers that students often encountered during the use of mobile devices were internet connectivity in the clinical settings, reliability of the information, and technical issues. Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed four themes: general usage by students, receptivity of the use of mobile devices by students, features in selecting resources for mobile learning, and limitation in the current use of mobile devices for learning.

Conclusion

The findings from this study assist in recommending suitable material using mobile devices to enhance learning in the clinical environment and expand the TAM 2.

Keywords: Mobile applications, Undergraduate medical education, Teaching rounds

Introduction

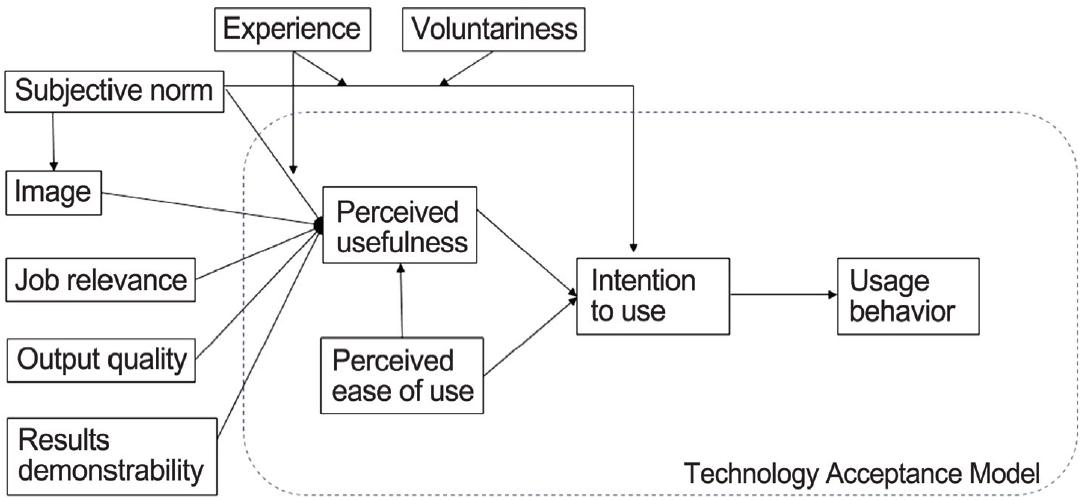

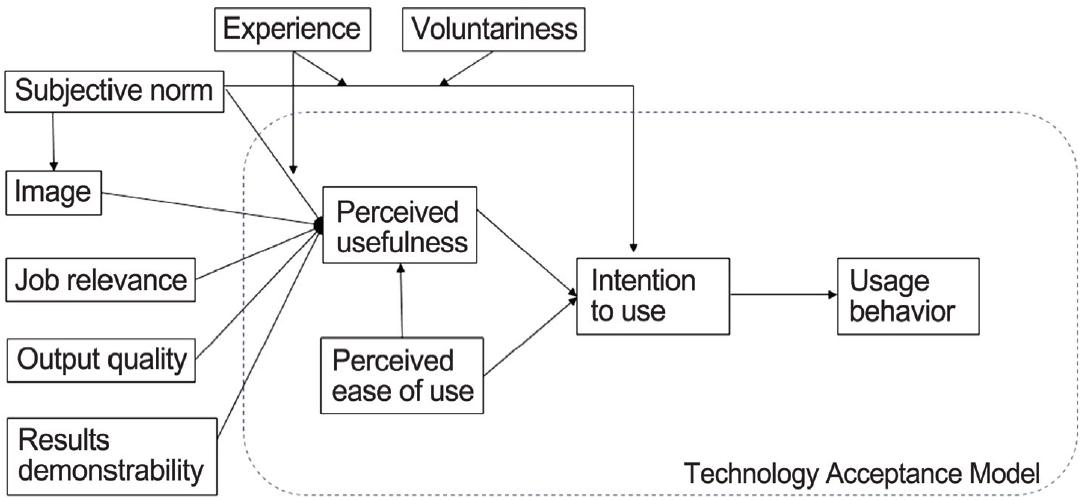

Digital technology presently shapes the way we live, learn, and play in most parts of the world. Smartphones and tablets allow us to access vast amount of information with ease without the constraints of time and place. In terms of learning, new generation of students are using their devices to access online material in real-time [ 1]. They prefer to apply immediately what they have learned to a real-life situation after engaging in hands-on learning opportunities. The nature of technology has helped the newer generation become more comfortable and accustomed to learning independently [ 2]. Therefore, medical education must change to accommodate new generations of learners and prepare them for entry into the practice of their chosen specialty [ 3]. Unlike other disciplines, medical students begin their clinical training at the hospitals from year 1 in their medical education journey. One of the chief complaints by teachers, especially at clinical training sites, is that students are using their mobile devices and getting distracted. The common assumption is that the students are not paying attention to bedside learning or expert sharing sessions by the clinical teachers but distracted by surfing social media on their devices [ 1]. However, according to studies, the most common use of mobile devices by students is to access information rapidly while in the clinical setting [ 1, 4- 7]. Other advantages of the use of mobile devices in the clinical setting include the acquisition and retention of new knowledge [ 8, 9], portability [ 4, 7, 10], and improved communications [ 11]. Common barriers mentioned were distractibility [ 1, 6], technical limitations [ 4- 6, 12], and the blurring of personal/professional boundaries [ 1, 4, 7, 11]. Much of the literature also investigate types of medical applications (apps) and resources on mobile devices [ 5, 10, 11, 13]. Despite a wealth of literature on the use of mobile technology in medical education, most literature focuses on the impact and perceptions of medical students, residents, and teachers [ 1, 5, 6]. The two papers which involved perceptions of patients are either focused on healthcare workers or on patient confidentiality in using mobile devices [ 14, 15]. Patients’ perceptions of using mobile devices in teaching and learning context are often neglected. It is important to explore perspectives of patients, as they are part of the clinical teaching process. Our research goes beyond current technical/functional aspects of mobile use and explores the doctors’ and patients’ in-depth perception towards the use of mobile devices in clinical settings among the students. The findings from this study will assist in informing and developing suitable materials and techniques to enhance learning in the clinical environment while interacting with patients. The findings might also be helpful in developing policy for the use of mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning setting. Mobile devices in this study context refer to any hand-held equipment, which is designed or capable of being used for telecommunication, including providing access to the Internet. Clinical teaching session or ward rounds refers to teaching and learning focused on, and usually directly involving, patients and their problem. The clinical environment consists of inpatient, hospital outpatient, and community settings [ 16]. The theory that underpins this study is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). This theory is widely used and the most influential theory for describing an individual’s acceptance of information systems in existing literature [ 17]. TAM was adapted from Theory of Reasoned Action [ 18] and first postulated by Davis [ 19] in 1986. Later, Venkatesh and Davis [ 20] proposed an extended version which is known as Technology Acceptance Model 2 (TAM 2). Based on their findings, Venkatesh and Davis [ 20] proposed that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are two main determinants that influence intention to use. There are a few variables that influence the perceived usefulness which were identify by Venkatesh and Davis [ 20], there are subjective norm (includes experience and volunteerism), image, job relevance, output quality, and result demonstrability ( Fig. 1).

Methods

This research employs an exploratory research design using survey and semi-structured interviews. Exploratory research design is defined as a “broad-ranging, purposive, systematic, pre-arranged undertaking designed to maximize the discovery of generalizations leading to description and understanding of an area of social or psychological life [ 21].” An electronic survey was distributed to all year 3 to year 5 medical students and medical residents on their perception about using mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning. Questions from the survey were derived from previous literature [ 5, 11- 13]. The questions were compiled and discussed by the authors in this study. The survey was then reviewed by an expert panel which consists of two medical educationalists and three clinical educators for content validity. The final questionnaire consists of 11 questions (four multiple choice questions and seven open-ended questions). This can be found in Appendix 1 [ 16, 22, 23]. All numerical data were entered and analyzed using the Microsoft Excel 2017 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, USA) as only descriptive statistics and multiple response analysis (for items no 1, 2, and 10) were performed. There were some open-ended questions from the surveys, which were initially coded and organized into key themes by the lead author, then verified by research assistant to support rigor and trustworthiness of the interpretation of the data [ 24]. To gain the perceptions of doctors and patients, semi-structured interviews with the doctors (who are clinical teachers as well), patients, and/or caregivers were utilized. These semi-structured interviews were guided by a list of questions developed by all authors after a review of the literature [ 16, 22, 23] ( Appendix 2). A convenience sampling was used: inviting voluntary participation in an interview through email. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by a research assistant, and compiled with field notes taken during the interviews. To ensure the trustworthiness of the data collected, the transcripts and field notes were analyzed by two coders using a thematic analysis approach to identify emergent ideas and concepts expressed by participants and ensure that data saturation had been achieved. ATLAS.ti 7 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was utilized to assist in the analysis process. A total of nine doctors and seven patients who expressed their interest were interviewed. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board in National University of Singapore (NUS-IRB approval code: B-16-279). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for the interviews and hardcopy survey. Implied consent was obtained when participants completed the survey online.This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board in National University of Singapore (NUS-IRB approval code: B-16-279). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for the interviews and hardcopy survey. Implied consent was obtained when participants completed the survey online.

Results

1. The survey

A total of 171 participants responded to the survey out of 900. Of these, 97% (n=166) are undergraduate clinical students from year 3 to year 5 while the remaining 3% are medical residents. Table 1 showed the different aspects of mobile phone usage in clinical setting in the survey. Items 1, 2, 3, 7, and 10 were multiple-choice questions while items 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 were open-ended questions. As expected, our students owned either an android phone or iPhone while some might have two mobile devices (android phone or iPhone with an iPad) at the same time (item 1). Hence, it is not surprising that the students accessed the information more than once per day (88%) (item 3) and the duration to find information is very quick which is less than 5 minutes to do so (item 5). Most of the time, students used mobile to find drug information and followed by practice guidelines but they did not really use it to look for and to read articles (item 2; please refer to Table 1 for the multiple response analysis). The reasons could be related to the barriers (item 10; please refer to Table 1 for the multiple response analysis), which will be described below. While 50% of the students preferred free resources, 40% of students still purchased mobile devices if it deems to be useful (item 7). While exploring the recent medical resources that the students used (item 4), the majority of the students picked UpToDate, which is a point-of-care medical resource, followed by Google. This was aligned with another open-ended question (item 8), which requires the students to rank their top 5 frequently used resources, UpToDate was ranked first and followed by Google, Medscape, Wikipedia, and e-Textbook.

Consistent with the reasons of using medical resources, when students were asked what works well and did not work well in an open-ended question (item 6), the three categories that emerged from what works well were user experience, enhanced learning and info quality. This coincided with item 9 whereby comprehensiveness and ease of access were the reason for their favorite resources. On the other hands, what did not work well was impaired internet connectivity in hospital and clinical settings. The other categories that emerged from this open-ended question were timeconsuming, technical issues related to mobile, poor accessibility, uncertain information searching, irrelevant or incomprehensiveness information, and tutor’s behavior. There are three technical issues related to mobile devices, which were again raised by the students including internet connectivity, mobile friendliness, and phone navigation. Table 2 shows some of the examples extracted from students input for each category. When students were asked about what types of medical resources that they wished the school/library to provide for their mobile device (item 11), two categories actually emerged from the data. Most of them named the online resources they required such as UpToDate, e-books, hospital guidelines, and anatomy applications. Some students, instead of requesting the applications to be available, listed the criteria of the resources they wished to have (second category). For instance, they would like to have resources that were simple and applicable to their year of learning as well as verified information as sometimes they are not sure the validity of the information. Some students would like the information or resources to be layered to their learning and more contextual resources, for instance, resources that were relevant for each posting to ensure the validity and reliability of the information while learning. This coincides with finding in item 10 whereby 52% of them would like to know the resources that are available out there for them.

2. The interviews

The above section summarized the quantitative data from the students’ perspective on the use of mobile devices in clinical setting. More interesting data surfaced via the qualitative data collection from doctors and patients. There are four themes that become apparent after the analysis: the general usage by students, which includes the frequency, purpose, and setting; receptivity of the use of mobile devices by students; features in selecting resources for mobile learning; and limitation in the current use of mobile devices for learning. The following paragraphs will illustrate these themes in detail.

1) Theme 1: usage by students

With regard to the usage by students, the frequency varies from none to frequent. For clinical teachers, the frequency might be due to their receptivity towards the use of mobile devices, which will be discussed in theme 2. As for patients, the use of mobile devices by the medical students was depending on patient-student contact time. The higher the contact hour with students in the bedside teaching and learning, the more frequent the patients observed the students using mobile devices as described in the excerpt below.

“There are many instances in the hospital that I was admitted so … there are some with two, some with four, some with six and I think the max was six … bedside is more frequent (seeing students using mobile devices) … Use it for 5 minutes.” (Patient 6)

When it comes to the purpose of using the mobile phone in clinical teaching and learning, the clinical teachers and patients are unsure as they did not scrutinize or seek student clarification when the students were using mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning setting. Hence, the data gathered ranging from information searching, taking down notes to personal use.

Patient 3: … those occasions, I noticed that they actually use the phone, I think take down notes or something like that. Interviewer: So you feel that they could be taking down notes? Were there any signs that you saw that they were taking notes? Patient 3: I think they are, because they look quite serious and trying to catch up with what the doctor is talking about. (Part of interview transcript with patient 3)

2) Theme 2: receptivity of the use of mobile devices by students

There were two eminent sub-themes shared by both doctors and patients on the receptivity of the use of mobile devices by students. The first sub-theme that was related to the use of mobile devices in a particular setting and purpose. Both doctors and patients dislike if the students were using mobile devices for their personal purpose. However, they could tolerate if students use it for the right purpose.

"… if they are checking a message, it’s probably inappropriate because it is very unlikely that a message is urgent.” (Doctor 6) “It’s fine if you’re using the thing for research and stuff. But if I happen to see that you’re not, like if it’s a social media site, then I will be disappointed.” (Patient 1)

Clinical teachers also listed out a few settings which was not acceptable to use mobile devices such as during structured clinical exercise or operating theatre. While clinical teachers were more concerned with the teaching and learning environment in determining the use of mobile devices; patients, on the other hands, are willing to accept that the learners use their mobile if consent was sought. This was related to the values (respect, etiquette, and courtesy) which will be discussed in the following sub-theme.

So coming back to this one, if they would like to use mobile devices, it would be better for them to seek permission, at least from their friends, their peers who are learning in the group to show some respects…” (Patient 2)

Although some doctors and patients were quite open for the students to use mobile devices in clinical setting, in fact, they will not stop students from using it, but deep down they actually felt it contradicted with the values such as respect, etiquette and courtesy. Hence, the second sub-theme that emerged is ambivalent between receptivity and values. This was especially prominent among patients. Here were some excerpts from the doctors and patients illustrating the dilemma that they have.

If I knew that they were using it for their personal purposes, I wouldn’t tell them off … but I will feel sad because the decorum that is required, the behavior that is required is expected to be tip top if you are going to be a doctor.” (Patient 7) It’s okay for me (but) it’s a bit disrespectful, to be honest. Being a tutor, I’m trying to teach them, educate them but I’ll expect some form attention being paid. If you’re not interested then that’s fine. But if you really want to learn then I think use the time (and) all these distractions can be put aside for a while if they are not urgent. (Doctor 9)

The third perspective, which could only be found in doctors’ data, was the teaching and learning philosophy. The philosophy that the clinical teachers perceived has an impact on their receptivity. The following were two contrasting philosophies that clinical educators have.

The point of the reflective questioning is for them to become aware of not only the specific gap and knowledge, but hopefully drive them to derive insight into the underlying weakness or poor habit, that led them to fumble with the question in the first place … The problem with the use of mobile phones in that regard, which is not something I allow is that it gives the person who’s frantically googling the answer, the tendency to brush aside those too critical questions, the reflective questioning.” (Doctor 3; resistant to the use of mobile devices in clinical setting) “Usually, they will look at all these search engines, medical online research engines, and then they will search for it and then they will actually challenge me literally challenge me as a form of discussion, which I truly enjoy and I truly welcome because I feel that, sometimes, there’s not enough information out there in the internet, (or) there’s a lot of information, some are real, some are justified.” (Doctor 2; receptive to the use of mobile devices in clinical setting)

From the above excerpts, we understood that one teacher believed that teaching and learning in clinical setting was about reflective questioning and “googling” the information will impede this skill. On contrary, another teacher thought that searching information allows the students to challenge tutors with more critical questions and that was how students learned. The difference in belief or philosophy in learning has enticed their acceptance towards the use of mobile devices among medical students.

3) Theme 3: the features of mobile learning resources

In spite of their receptivity, the clinical teachers did acknowledge some good mobile resources for the students. There were no absolute resources suggested by clinical teachers as they have different perceptions even towards the same resources. However, the common features of a resource shared by the participants were discussed below.

a. Harmonisation of the content

A good mobile resource, according to the teachers, would provide the learners what is necessary but in a structured and concise manner as well as not to overwhelm the learners by having additional links for learners to proceed further if they would like to.

b. Appropriate method of using resources

Regardless of how good a mobile resource is, clinical teachers felt that it should be used in an appropriate manner. Instead of telling learners to follow instructions and obtain the answers, clinical teachers played a vital role in explaining how to use the results in different scenarios.

“There’s online calculators A and B, what you want to let them know is not just to look at the results and blindly follow it, but to realize that the clinical decision rules inside have a certain context to it. They would have one-way rules, for example, that leads you to a discussion on what evidence-based medicine, and Bayesian probability thinking and all that. And that actually is an interesting discussion to have with the students. So it’s not just telling them that there’s this website whose results you put in and then you spit out something and then you follow it blindly, but rather how to use that result in context.” (Doctor 9)

4) Theme 4: limitation in the current use of mobile devices for learning

The use of mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning was not uncommon, yet, there were still constraints raised by the participants. The biggest limitation disclosed by the clinical teachers was the students themselves finding valid and useful resources the learners to address their gap.

“I think sometimes students are not very selective about the references they use or the websites. Some of my students tell me the website, half the papers there are like…. [laughs]. So sometimes, as students, we are not very aware of the reputation until I realized these papers don’t make sense.” (Doctor 8)

The clinical teachers were able to rectify the validity of the resources if the materials were shown to the teachers; however, it was not the case every time. We believed students were aware of this limitation; therefore, they requested to have some recommended resources in every posting (refer to quantitative data). Other than the validity of the resources, clinical teachers also shared the struggle students might face in searching for information online.

“I think that’s where the struggle really is for them (the students). Pulling the information from the internet can be useful for them, but that is if they find, if they are aware of the knowledge gap that exist in the first place. If they are not aware of what, exactly they should be looking for that online search sometimes may not be as useful.” (Doctor 9)

The second limitation brought up by the clinical teachers is the ill-suited access of resources for different learners provided by the school.

“To be honest, until now, I still find, having papers’ access is very difficult. Like journals, all that stuff. They gave it to students who don’t know how to use it, then when you go become a doctor and I need this, but now I don’t have it.” (Doctor 5)

From the above transcript, journal articles were not persistently required by medical students as compared to residents. However, access to journal articles by the residents was limited as mentioned by the clinical teachers. The third limitation was related to the policy on the use of mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning.

“And I’m also not sure if schools have a policy on this, which would have been helpful to manage. My perspective is that it is not so much the device that is the problem, it is about how it is being used and whether there are clear instructions on that. I think if there are clear instructions, it would go a long way to making this a positive.” (Doctor 1)

From the data reviewed, we understood that there was no such policy put in place yet. Hence, this was an ambiguous area that the clinical teachers will need to deal with.

Discussion

sed as a learning tool by medical students in clinical settings. However, the perceptions among their clinical supervisors and patients were varied. Since the social interaction is always a three-way process between student, teacher, and patient in clinical training, this will increase the complexity of using mobile devices [ 1]. Based on the survey, the use of mobile devices was best suited for searching information due to its comprehensiveness, quick access, and ease in using. This is similar to other research whereby providing quick access is the main reason in using mobile [ 5, 10]. This is aligned with TAM 2 whereby the output quality the extent to which the technology adequately performed the required tasks) and result demonstrability (the production of tangible results) will influence the perceived usefulness of the technology. The information that students regularly look into using mobile devices are drug information, practice guidelines, and clinical calculation. While searching for drug information was common in the existing research [ 5, 11, 25, 26], students do not really take notes using mobile devices as reported in other studies [ 5, 26]. This is not surprising as Archibald et al. [ 10] in his research found out that users still preferred a laptop or desktop if typing a long text is required. However, considering the current mobile devices now equipped with better screen size, screen display, and technology nowadays, it is expected that higher number of students will search and read journal article using their phone [ 5]. However, this was not the case in our study. TAM 2 might be able to provide us a possible reason on this. Job relevance, as mentioned in the theory, will influence the intention to use and usage behavior. Since accessing the latest journals during their clinical training in undergraduate years might not be required, students using mobile phone to search and read for article does not seem to be popular. The most constantly used application is UpToDate, which is also aligned with the study conducted by Boruff and Storie [ 5] and Prgomet et al. [ 27]. Smartphones in clinical environment are always used for point of care. As such, a mobile application that can increase efficiency by saving time and allowing rapid decision making will be popular [ 11]. Similarly, students used Google more often than other free resources such as Medscape and Epocrates. One possible explanation mentioned by Boruff and Storie [ 5] and in the open-ended question on barriers was Google provided the students immediate search results without requiring the students to log-into library-licensed resource such as UpToDate and PubMed. This allowed them to have quick access to answers for some questions less than 5 minutes. Despite the positive attitudes towards the use of mobile devices among the students, the internet connection speed in hospital was far below the expectations, which frustrated the learners. This is not an unusual phenomena as other studies have also indicated the connectivity is the major barrier in mobile learning [ 4, 5, 7, 28]. Hence, in order to support the use of mobile devices in teaching and learning in clinical setting, having a stable and good connectivity will be the priority. Having said that, connectivity is not the only technical barrier encountered by the learners. Although some mobile applications are mobile friendly, the interface for typing and searching keywords within a document have not reached a mature operational stage to facilitate navigation of the content. In spite of the advancement in mobile technology, this issue remained since 2014 in a study published by Archibald et al. [ 10]. Besides the mobile hardware barriers, which impact the use of mobile devices in clinical setting, our findings also revealed human-related barriers which were neglected in the existing literature. A tool is only as good as the person using it or knowing how to use it to maximize its benefits. However, from student survey and clinical teachers’ interview data, we understand that students often experienced uncertainty in selecting valid and appropriate resources due to the massive amount of information on the web these days. Therefore, selecting the best and valid resources is not that straightforward as illustrated by clinical teachers. Learners will need to be aware of their learning gap, which involves self-reflection and metacognition in order to select the most suitable resources. It is not surprising that students indicated difficulty in selecting valid resources and spending more time in searching for relevant information. Recommendation by experts, which was also requested by students, might be one of the solutions to mitigate the above issue.

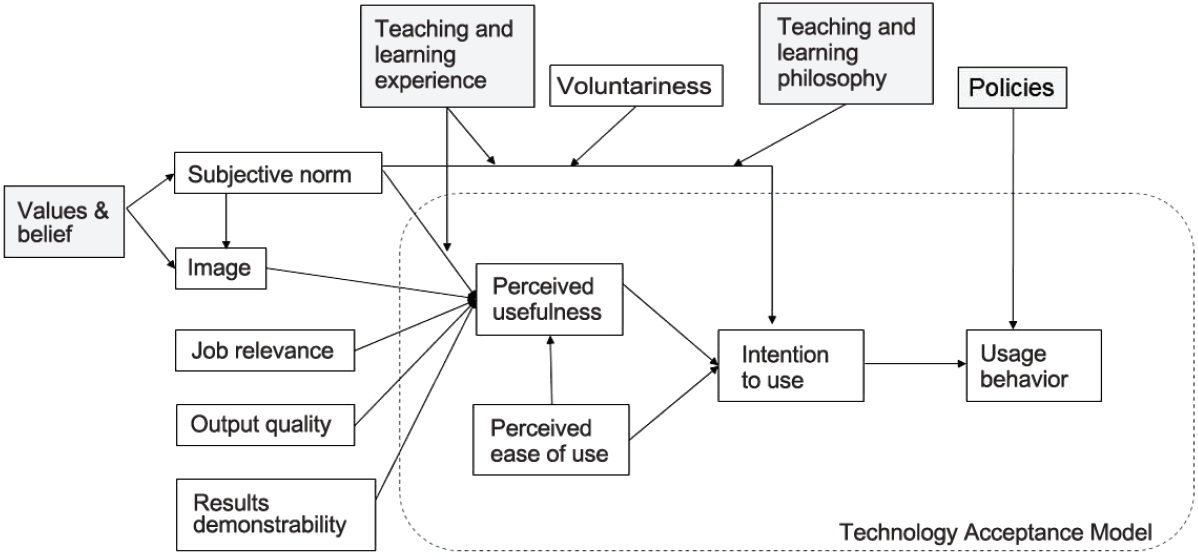

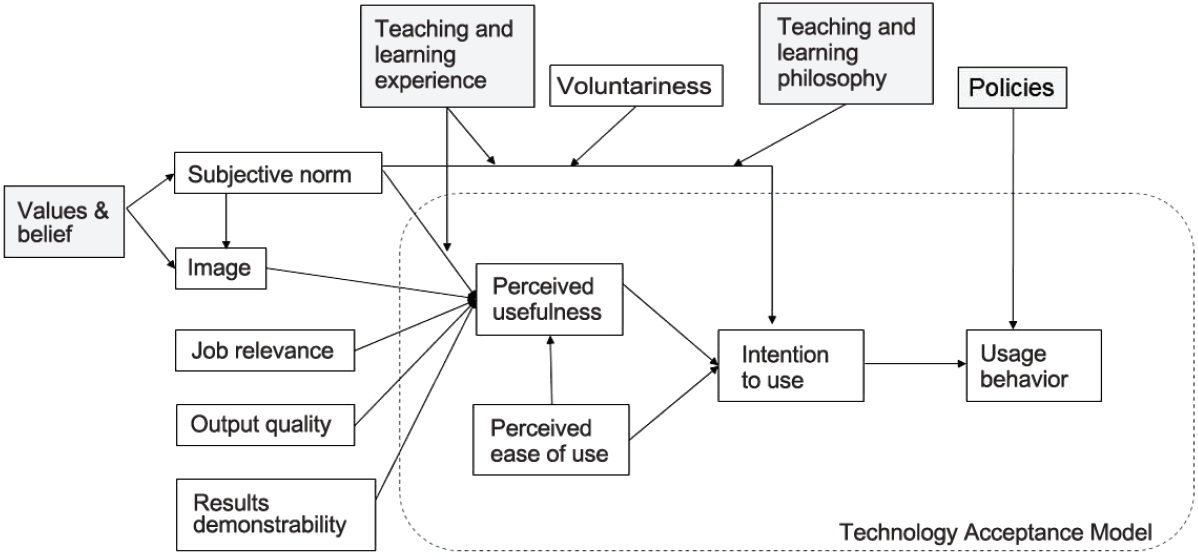

An incongruency was observed by the clinical teachers on the resources provided to different learners. An example illustrated above was that the use of journal articles was essential to residents but not medical students, yet this facility was only provided to medical students. Similar issue was also discussed in a study of Boruff and Storie [ 5]. Unfettered access to information using mobile devices may also lead to some dilemma in workplace such as when is the appropriate time to read messages and what is considered an appropriate use of mobile devices in clinical environment. Ambiguous or ill-defined policy in this aspect might be challenging the distinction between personal and professional usage as mentioned by the clinical tutors as one of the barriers. Some studies anticipated that health organizations may eventually provide work-only mobile devices [ 29, 30] or a definite policy from the organization is required [ 11] to resolve the above dilemma. While the students are quite positive about the use of mobile devices in clinical setting, this might not be the case for doctors and patients. The receptivity on the use of mobile devices in clinical teaching and learning varies. Nonetheless, the findings on why some teachers are more receptive than the others are interesting and can be contributed to the existing literature and TAM 2, which to our own understanding this has not been explored elsewhere. Patients might appear to be receptive and open-minded in the beginning of the interview, but they also emphasized the importance of values in using mobile devices in clinical setting when probed further. Respect, etiquette, and decorum were the values that the patients and doctors keep mentioning during the interview. This might be related to the culture in the Asian culture whereby strong emphasis is given to family connection and filial piety and respect for one’s parents and elders is critically important [ 31]. However, feeling rude and disrespect is not specifically unique in the Asian context, a study carried by Bullock [ 32] has also been reported similar outcome by both patients and hospital staff. In the study carried out by Rashid-Doubell et al. [ 1], students felt dissonance as to the legitimate use of mobile devices in front of clinical tutors in clinical setting as tutors might be receptive or resistant towards the use of mobile devices. Based on the evidence, the attitudes were highly based on the setting and the clinical teachers’ teaching and learning philosophy. Certain settings which require the engagement of students with patients and the tasks, mobile devices are prohibited unless with teachers’ permission. Similarly, how the teachers think of teaching and learning would determine their acceptance towards the use of mobile devices in clinical environment. Teachers resisted the use of mobile devices; worrying that students will not be able to concentrate and acquire reflective questioning which is crucial as a future doctor. This is contrary to the benefits published in the current literature review stating that mobile learning actually helps in acquiring and in retention of new knowledge. While we acknowledge that googling every answer might deter students to become a reflective learner, how teachers could leverage the strengths of mobile devices and facilitate students to attain higher-order thinking skills is something that the faculty could help the teachers to work on. Based on the above findings, we have further expanded the TAM 2 as shown in Fig. 2.

1. Strengths and limitation

Using a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection methods enabled us to obtain different perspectives from three different groups and triangulate the data. In addition, the qualitative data from clinical educators and patients have added to the richness of the data especially in the receptivity aspect, which was neglected in current literature.

Having said that, we encountered some limitations in this study mainly the low response rate from the students. The sample size may be considered small for clinical educators and patients due to low take up rate during the recruitment; however, we ensure the crystallization of the data has reached before ceasing the recruitment. Therefore, attempting to generalize our findings to a different population or different context may not withstand scrutiny. We aim to increase this generalizability by comparing and contrasting similar research done in other parts of the world and some of the findings concurred with ours.

2. Conclusions

We cannot stop and deny the ever-growing use of mobile devices in medical education. However, we could prepare faculty, students and other stakeholders based on the outcome of this study. The results of our findings have provided us with an insight into the perceptions of how our medical students use mobile devices in a clinical setting. The findings coincide with the other similar research in other parts of the world. Apart from technical barriers mentioned by the students, there are also some human-related barriers that could possibly complicate the use of mobile devices in clinical settings.

The qualitative data, on the other hands, tell us more about doctors’ and patients’ view on students using mobile devices in a clinical setting especially on receptivity. Values such as respect, decorum, and etiquette are perceived highly by our patients although they are quite receptive about the use of mobile devices among the students. Teaching and learning philosophy, as well as different setting, will have an impact on teachers’ receptivity. Therefore, using mobile devices in a clinical setting is not so straightforward due to the abovementioned elements. In addition, the lack of clear policy and training of students and teachers on this aspect might impede the use of mobile devices to maximize learning. It is also important for healthcare leaders to be part of the conversation to mitigate the barriers and provide useful resources for better learning.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ruth Jamie Teo and Kaludewa Lilusha Ranwala assisted in formatting of this paper. We appreciate the participation of the patients, faculty members, and medical students in this research.

Fig. 1.

Technology Acceptance Model 2

Fig. 2.

Technology Acceptance Model 2 Based on the Findings from This Study

Table 1.

Different Aspects of Mobile Phone Usage in Clinical Setting

|

Items |

No. of respondents |

% of respondents |

% of cases |

|

Item 1: Types of devices own |

|

|

|

|

|

iPhone or iPod Touch |

103 |

38.7 |

60.2 |

|

iPad |

73 |

27.4 |

42.7 |

|

Other tablets |

22 |

8.3 |

12.9 |

|

Android phone |

65 |

24.4 |

38.0 |

|

Blackberry |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Other phones with internet access |

3 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

|

Total |

266 |

100.0 |

155.6 |

|

Item 2: Usage of mobile device during clinical teaching sessions or ward rounds |

|

|

|

|

Take notes |

128 |

14.2 |

75.3 |

|

Find drug information |

144 |

16.0 |

84.7 |

|

Find practice guidelines |

135 |

15.0 |

79.4 |

|

Read point-of-care information |

115 |

12.8 |

67.6 |

|

Clinical calculations |

115 |

12.8 |

67.6 |

|

Differential diagnosis |

107 |

11.9 |

62.9 |

|

Search for journal articles |

70 |

7.8 |

41.2 |

|

Read journal articles |

63 |

7.0 |

37.1 |

|

Others (refer to e-Book, for clarification, send pictures, Google information & contact staff) |

22 |

2.6 |

13.5 |

|

Total |

899 |

100.0 |

528.8 |

|

Item 3: Frequency in accessing medical resources |

|

|

|

|

More than one a day |

151 |

88.3 |

|

|

Once a day |

7 |

4.1 |

|

|

Several times in a week |

9 |

5.3 |

|

|

Several times in a week |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

Once a month |

1 |

0.6 |

|

|

Less than once a month |

1 |

0.6 |

|

|

Never |

0 |

0.00 |

|

|

Total |

171 |

100.0 |

|

|

Item 4: Recent medical resources using a mobile device |

|

|

|

|

Google |

37 |

21.5 |

|

|

ECG on Life in the FASTLANE |

5 |

2.9 |

|

|

e-Books |

3 |

2.0 |

|

|

MDCalc |

3 |

2.0 |

|

|

UpToDate |

75 |

44.1 |

|

|

Wikipedia |

10 |

5.9 |

|

|

Medscape |

15 |

8.8 |

|

|

Radiopaedia |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

WebMD |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

PubMed |

5 |

2.9 |

|

|

Mayo Clinic |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

Orthobullets |

5 |

2.9 |

|

|

BMJ |

3 |

2.0 |

|

|

Merck Manual |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

One Note |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

Total |

171 |

100.0 |

|

|

Item 5: Duration to find information |

|

Less than 5 minutes |

|

|

Item 6: What worked or did not work well? |

|

Refer to Table 2 |

|

|

Item 7: Number of purchased medical resources |

|

|

|

|

None |

93 |

54.4 |

|

|

1–4 |

68 |

39.8 |

|

|

5–10 |

6 |

3.5 |

|

|

>10 |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

No responses |

2 |

1.2 |

|

|

Total |

171 |

100.0 |

|

|

Item 8: Five medical resources that the students use most frequently |

|

|

|

|

UpToDate |

134 |

28.0 |

|

|

Google |

37 |

8.0 |

|

|

Medscape |

36 |

8.0 |

|

|

Wikipedia |

34 |

7.0 |

|

|

E-Textbooks |

22 |

5.0 |

|

|

Total |

263 |

56.0 |

|

|

Item 9: Reasons for using favourite medical resources |

|

|

|

|

Free |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

Corroborates with what I’m using to study |

2 |

1.0 |

|

|

Quick access (portability) |

10 |

6.0 |

|

|

Consolidate information |

21 |

12.0 |

|

|

Validated, credible, and reliable |

36 |

21.0 |

|

|

Easy to use and convenient |

48 |

28.0 |

|

|

Comprehensive and informative |

53 |

31.0 |

|

|

Total |

171 |

100.0 |

|

|

Item 10: Barriers encountered when accessing medical resources |

|

|

|

|

Wireless access in the hospital/clinical |

134 |

33.3 |

80.2 |

|

Knowing what resources are available |

87 |

21.6 |

52.1 |

|

Understanding how to use the resources |

35 |

8.7 |

21.0 |

|

Technology problems |

19 |

4.7 |

11.4 |

|

Complication installation process |

12 |

3.0 |

7.2 |

|

Do not have permission to install software |

34 |

8.4 |

20.4 |

|

Lack of time |

55 |

13.6 |

32.9 |

|

Others (cost, poor navigation, tutor disapproval, unreliable, technical issue, administrative hassle) |

27 |

6.7 |

16.2 |

|

Total |

403 |

100.0 |

243.1 |

|

Item 11: Medical resources the students would like the school/library to provide |

|

|

|

|

Online resources |

UpToDate, medical journals, Osmosis, BMJ, Medscape, Complete Anatomy, Essential Anatomy, Amboss, Anki, drug list, BMS, TeachMeAnatomy, AccessMedicine, MedCalc, USMLE resources, radiology images, anatomy apps, various medical apps, MIMS, Notes, Notability, GoodNotes |

|

Features of the resources |

- Information by topic/disease that is layered into what we are expected to know at each level and maybe even for each posting. |

|

- List of recommended medical resources for each posting |

|

- An official app with consolidated and verified information |

|

- An app that summaries important concepts with diagrams of what we’ve learnt/what could be useful in the future. |

|

- Mobile app that gives us all the access with one login (and stays open in the app) so we don’t have to keep logging in to the various medical resource websites. |

|

- School notes in an application. |

|

- School recommended reading material for every topic we should know. |

|

- Some resource that caters specifically to medical students with simple, applicable information. |

Table 2.

Category on What Worked and What Did Not Work While Using Mobile Devices?

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Example |

|

What worked? |

|

|

|

|

User experience |

Fast and efficient |

"It was efficient and quick to use." |

|

Accessible & convenience |

"Information is easily accessible." |

|

Info quality |

Reliable, relevant, and simplicity |

"The information is reliable, relevant and easy to understand." |

|

Breath of info |

"UpToDate has a lot of information. It is so comprehensive…" |

|

Enhance learning |

|

It enabled me to understand. |

|

What did not work? |

|

|

|

Time-consuming |

|

"UpToDate has a lot of information. But because it is so comprehensive, sometimes we waste a bit of timing reading up about things that are not as important to us." |

|

Technical issues related to mobile devices |

Internet connectivity |

"It works, provided there’s Wi-Fi." |

|

Mobile friendliness |

"Some sites do not support mobile viewing." |

|

Navigation |

"Hard to browse through pages, no control Ffunction on phone to find info I need quickly." |

|

Poor accessibility |

|

"It worked well but sometimes protocols between hospitals differ and their guidelines are not always accessible." |

|

Uncertain information searching |

|

"When there are many search results don’t know which is most accurate/appropriate." |

|

Irrelevant or incomprehensive information |

|

"A lot of resources are US-based, not local." |

|

Tutor’s reaction toward the use of mobile devices |

|

"But it’s harder if the tutor does not allow us to use." |

References

2. Seemiller C, Grace M. Generation Z: educating and engaging the next generation of students. About Campus 2017;22(3):21-26.  3. Boysen PG 2nd, Daste L, Northern T. Multigenerational challenges and the future of graduate medical education. Ochsner J 2016;16(1):101-107.   4. Davies BS, Rafique J, Vincent TR, et al. Mobile Medical Education (MoMEd): how mobile information resources contribute to learning for undergraduate clinical students: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ 2012;12:1.   9. Briz-Ponce L, Juanes-Méndez JA, García-Peñalvo FJ, Pereira A. Effects of mobile learning in medical education: a counterfactual evaluation. J Med Syst 2016;40(6):136.   12. Subhash TS, Bapurao TS. Perception of medical students for utility of mobile technology use in medical education. Int J Med Public Health 2015;5(4):305-311.  13. Koh KC, Wan JK, Selvanathan S, Vivekananda C, Lee GY, Ng CT. Medical students’ perceptions regarding the impact of mobile medical applications on their clinical practice. J Mob Technol Med 2014;3(1):46-53.  14. Alexander SM, Nerminathan A, Harrison A, Phelps M, Scott KM. Prejudices and perceptions: patient acceptance of mobile technology use in health care. Intern Med J 2015;45(11):1179-1181.   16. Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach 2008;30(4):347-364.   17. Lee Y, Kozar KA, Larsen KR. The technology acceptance model: past, present, and future. Commun Assoc inf Syst 2003;12(Article 50):752-780.  18. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

19. Davis FD. A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results [dissertation]. Cambridge, USA: MIT Sloan School of Management; 1986.

20. Venkatesh V, Davis FD. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manag Sci 2000;46(2):186-204.  21. Stebbins RA. Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, USA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2001.

23. Road Traffic Act. Chapter 276 (Jan 1, 1963).

24. Grbich C. Qualitative research in health: an introduction. London, UK: Sage; 1999.

25. Grasso MA, Yen MJ, Mintz ML. Survey of handheld computing among medical students. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2006;82(3):196-202.   28. Witt RE, Kebaetse MB, Holmes JH, et al. The role of tablets in accessing information throughout undergraduate medical education in Botswana. Int J Med Inform 2016;88:71-77.   29. Hagland M. Handheld juggernaut. Healthc Inform 2010;27(8):8.

30. Phillippi JC, Buxton M. Web 2.0: easy tools for busy clinicians. J Midwifery Womens Health 2010;55(5):472-476.   32. Bullock A. Does technology help doctors to access, use and share knowledge? Med Educ 2014;48(1):28-33.

|

|