Differences and changes in the empathy of Korean medical students according to gender and vocational aptitude, before and after clerkship

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to determine whether there is any change in the empathy scores of third-year medical graduate students after they have taken a clerkship and have begun gaining more opportunities to meet patients through the clerkship.

Methods

The participants were 109 third-year students in 2014 and 110 fourth-year students in 2015 at Kyungpook National University, School of Medicine. The author measured empathy using a modified and expanded version of the Korean version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy of Physician Empathy-Student version and used the Holland-III aptitude test-S to assess vocational aptitude.

Results

As a results, male students in their third year exhibited higher scores, but there was no significant difference in the fourth year. The empathy score increased slightly when third-year students became fourth-year students, but the difference was not statistically significant. There was no statistically significant change in the scores of both male and female students between the 2 years. The results of the vocational aptitude test showed that students who preferred person-oriented specialties had higher empathy scores when they entered their fourth academic year compared to objectively-oriented students.

Conclusion

In this study, male students showed higher empathy scores than female students, an atypical finding that was inconsistent with the results of previous studies. However, the distribution of scores among male students was wider than that of female students, a finding consistent with previous studies. As such, individual differences need to be considered when developing curriculum in order to improve the empathy of medical students.

Introduction

Empathetic ability is one of the essential competencies required of physicians [1,2]. This is as important as clinical performance competency for future physicians [1,3]. The physician’s empathy affects the outcome of treatment [3], the patient’s satisfaction [4], and the physician’s satisfaction [3,5]. For this reason, empathy is defined as one of the core learning outcomes of medical school in the “Learning outcomes of basic medical education: human and society-centered” published by the Korea Association of Medical Colleges. With this in mind, many medical schools in Korea seek to foster students with empathetic abilities, and are using various courses in different grade levels to achieve this learning outcome.

However, various studies on the empathy of medical students show conflicting results. Some studies suggest that students show higher empathy scores in their final year than their initial year [6], while other studies suggest that there is no difference according to the academic year [7,8], or that students in upper years show lower empathy scores than those in lower years [2,9,10]. In particular, some studies have found that empathy scores tend to increase according to the academic year, but decrease in the final year [11,12]. Many studies have shown that the level of empathy significantly decreases during clinical clerkship, even though practical training should be provided to improve the students’ empathy during this period, since students are meeting patients in person to practice medicine.

After studies reported that students’ empathy abilities decline as they move on to an upper grade, many studies have been conducted to determine the reasons for this [2,5]. One study analyzed possible factors that may change empathy levels according to the academic year [2], while a systematic review study found that “informal” and “hidden curriculum” affected students’ empathy [10], and another study suggested a developmental trajectory of empathy at the beginning of clerkship using qualitative analysis of a hidden curriculum [13]. As such, changes in students’ empathy during the clinical year is one of the major concerns.

Gender is one of the variables that continues to be analyzed in research related to empathetic ability [1]. In terms of the difference in empathy scores between males and females, some studies found no gender-specific difference [7,14], while other studies in many countries have shown that female students have higher levels of empathy than male students [12,15,16]. Even in studies on physicians, female physicians showed higher empathy scores than male physicians [17,18]. Due to the conflicting results of previous studies, the gender difference is one of the factors that needs to be examined in research related to empathy.

In addition, several other factors were found to influence empathy scores, while age [7,15], academic performance [19], and club activities [7] were found to have no associations with empathy. Meanwhile, studies related to specialty preferences and empathy scores suggested that students who chose person-oriented specialties (e.g., internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, and so forth) had higher empathy scores than students who chose object-oriented specialties (e.g., surgery, anesthesiology, radiology, and so forth) [8,12,19]. One of these studies found that the higher empathy scores shown by students who chose person-oriented specialties were accounted for by the higher number of female students majoring in this field [12]. In another study on physicians, physicians in person-oriented specialties had higher empathy scores than those in other departments [18]. As seen above, many studies have been conducted to define the concept of empathy in Korea [7,9] as well as in other countries around the world [20], to measure empathy levels [2,6], to analyze factors and causes that affect empathy [10,13] and to develop methods to maintain and enhance empathy ability [1,21,22].

However, those studies measured the empathy levels of students at a certain point in time in different grades to compare their empathy levels based on grade, gender or personality. There were few studies that measured the empathy levels of students in the same school year to analyze whether a change in empathy levels occurred before and after the clerkship. Moreover, it was difficult to find such studies conducted in Korea. In addition, despite the findings of previous studies that the empathy scores of students increase as they advance to upper grades and then decrease in the final year, few studies have measured changes in empathy before and after clinical practice.

As such, the purpose of this study was to analyze the changes in empathy scores according to gender and vocational aptitude in the clinical year, focusing on the results of previous studies which suggest that empathy scores tend to decrease in the final year. The author chose gender as an independent variable because it has been continuously addressed in studies related to empathy, and also because conflicting results were derived not only in Korea but also in other countries. In addition, although various studies in other countries found differences in empathy scores according to preferences for person-oriented specialties or object-oriented specialties, there is no precedent for such research in Korea, so it would be significant to investigate vocational preference in this study. Thus, this study aims to analyze whether there is a change in empathic ability according to gender and vocational aptitude before and after experiencing clerkship in Korea.

Methods

Data were collected from 109 third-year students of 2014 and 110 fourth-year students of 2015 at Kyungpook National University, School of Medicine (KNUSOM) using the Jefferson Scale of Empathy of Physician Empathy-Student version (JSPE-S). After conducting the JSPE-S and the Holland-III aptitude test-S on third-year students in 2014, the author performed the same tests on the same students in 2015 when they became fourth-year students.

KNUSOM was turned into a 6-year medical school from a 4-year graduate medical school in 2015. The 6-year medical course consists of 2 years of pre-medical school and 4 years of medical school. After completing pre-medical school, the students go through basic medicine and clinical medicine courses for the first and second years of medical school, and clinical training for the final 2 years. Participants in this study were students from 4-year graduate medical school who did not go through the pre-medical courses.

The participants took part in this study voluntarily after the student representative explained the purpose and intent of this study to them. The participants answered anonymous, self-administered questionnaires.

The participants consisted of a total of 219 third-year students in 2014 and fourth-year students in 2015. The author analyzed the questionnaires of 185 students who faithfully responded. In 2014, 96 (88.1%) out of 109 third-year students participated in the tests, of which 80 (73.4%) were selected for the analysis once 16 who gave insufficient information or did not agree to the use of data were excluded. In 2015, 107 (97.3%) out of 110 fourth-year students participated in the tests, of which 105 (95.5%) were selected for the analysis once 2 who gave insufficient information were excluded. The reason for the different number of participants in 2014 and 2015 was attributed to the fact that voluntary participation was relied on. Although the response rate was high in 2014, many of the participants did not agree with the use of the survey results or gave insufficient information.

The JSPE-S was used to evaluate the empathy level of students. This is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring empathy which is used in many countries around the world [9,21,23]. The Korean version is validated and is currently used in Korea (Cronbach’s α=0.84) [24]. The original version includes 20 questionnaire items. However, two of the items were excluded in this study’s measurement tool because they were considered inappropriate for cultural reasons, resulting in 18 items in the questionnaire. Each item was answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), so the lowest possible score is 18 points and the maximum is 126 points. The 18 questions about empathy are divided into three sub-categories, in which items 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, and 18 are about “perspective taking”; questions 1, 7, 8, 11, 12 and 14 are about “compassionate care”; and items 3 and 6 are about “emotional detachment” [24].

The Korean version of the Holland-III aptitude test-S was used as the instrument to measure vocational aptitude in this study [25]. This is an aptitude test developed by John L. Holland that uses self-reporting and is based on trait-factors theory. The test assumes that the level of job satisfaction will be high when an individual’s traits match his or her preferred vocational environment [26]. The test classifies personality types into six types: realistic type, investigative type, artistic type, social type, enterprising type, and conventional type (RIASEC), and presents the preferred vocational majors and careers by each type. This instrument has been widely used in studies related to medical specialty choices [27,28], and is considered to be a suitable tool for examining the future specialty aptitudes of medical students. This study also classified the six personality types into person-oriented and object-oriented traits, and compared the differences in empathy scores according to these two traits [27]. Among RIASEC, the author classified artistic, enterprising, and social types as person-oriented types, and realistic, investigative, and conventional types as object-oriented types [27]. As for the corresponding vocational environments, the author divided the departments of hospitals into person-oriented and technical-oriented specialties based on well-established categories in prior studies [11,19]. Clinical departments that prevent, diagnose, treat, and manage the prognosis of diseases by interviewing patients such as internal medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, and family medicine were classified as person-oriented specialties, while departments such as surgery, radiology, and pathology, which require highly skilled and specialized therapeutic techniques or procedures were classified as technical-oriented specialties [11,19]. This study also examined general characteristics including the age and gender of the participants.

Frequency analysis was conducted on the general characteristics of the students, such as age, gender, and vocational characteristics. The normal distribution of variables was verified by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, but the results suggested abnormality. Thus, the non-parametric test was used. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to verify differences between two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to verify differences between three groups or more. IBM SPSS ver. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) was used for statistical analyses of the data, the graphs were created using R ver. 3.5. ggplot2 packages (https://www.r-project.org/), and the significance was declared at p<0.05. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Industry Foundation (IRB approval no., 2018-0174).

Results

1. The demographic characteristics of the students

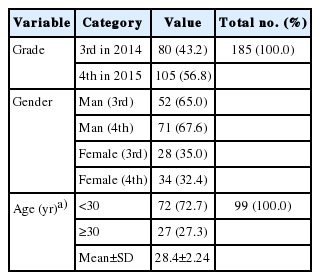

Eighty out of 109 third-year students who participated in the survey were selected for the analysis in 2014, including 52 males (65.0%) and 28 females (35.0%). In 2015, after they became fourth-year students, 105 who participated in the survey were selected for the analysis, including 71 males (67.6%) and 34 females (32.4%) (Table 1). In terms of vocational aptitude types, 22, 15, 10, 20, 2, and 11 respondents among the third-year students belonged to realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional types, respectively, while among the fourth-year students, 36, 24, 11, 21, 3, and 10 respondents were classified to the respective types. Therefore, most of the students were found to be realistic types. The author could not confirm changes in the vocational aptitude types of individual students by grade because the survey was conducted anonymously. However, there was no significant change in vocational aptitude type by year when the whole group was considered (Table 2). When the students were classified into person-oriented and object-oriented types, 32 of the third-year students and 35 of the fourth-year students were found to be person-oriented types, and 48 of the third-year students and 70 of the fourth-year students were found to be object-oriented types. When the age of students in the fourth year was examined, about 73% (72 people) were under 30 years old (Table 1).

2. Distribution of empathy scores

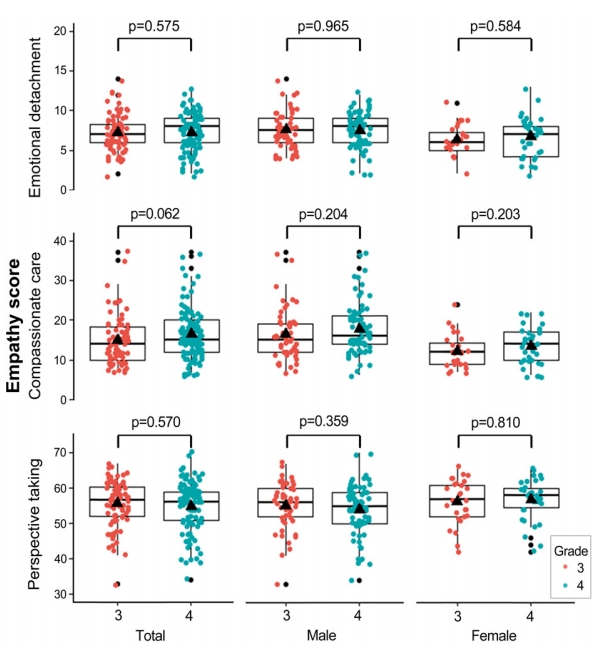

In 2014, the mean empathy score of third-year students was 77.6 points (standard deviation [SD]=8.47) and the median was 76.0 points (minimum=57, maximum =108). A year later, when they became fourth-year students, the mean empathy score was 78.5 points (SD=7.29) and the median was 78.0 points (minimum=66, maximum=105). The majority of students scored between 70 and 79 points, and 48 third-year students (60%) and 58 fourth-year students (54.2%) were in that range (Fig. 1). When third-year students entered their fourth year, their median empathy score increased slightly, but not to a statistically significant extent (Fig. 1).

3. Gender differences in empathy and changes in empathy scores between males and females as grades change

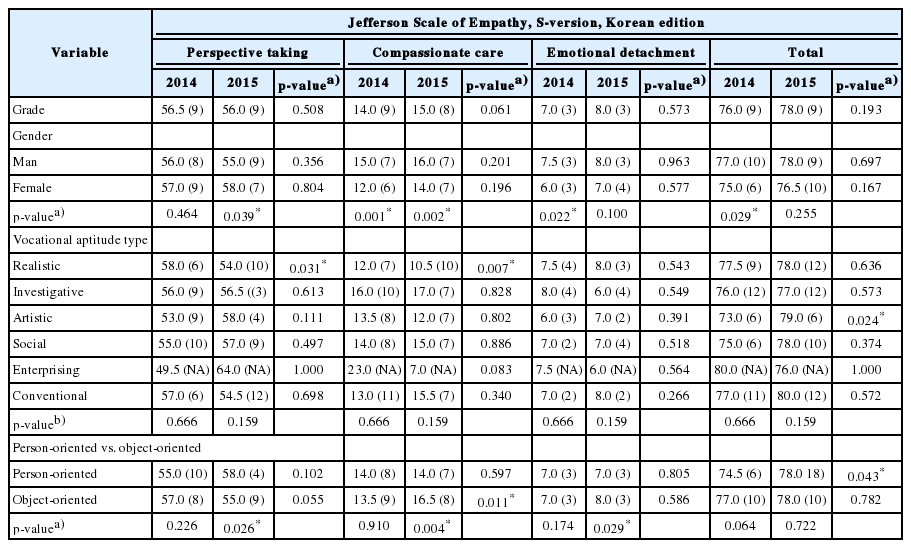

Looking at the difference in total empathy scores by gender, the total scores of male students were significantly higher than those of female students in 2014. However, there was no significant difference in 2015. Even in 2015, the empathy scores of male students were relatively higher than those of female students, although the difference was not significant (Table 3). In three sub-categories, the scores of female students were higher than those of male students in the area of “perspective taking,” although the difference was not significant. In contrast, in areas such as “compassionate” and “emotional detachment,” male students showed higher scores than those of female students, though again, the difference was not significant (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Differences in Empathy Scores by Gender, Vocational Aptitude, and Person-Oriented/Objected-Oriented Vocational Characteristics, and the Changes in Empathy Scores after Clerkship

The mean score and median of male students were 79.2 points (SD=9.69) and 77.0 points (57–108), respectively, in 2014, and were 79.3 points (SD=7.71) and 78.0 points (67–105), respectively, in 2015. Over the 2 years, their scores ranged from 57 to 108 points. The mean score and median of female students were 74.7 points (SD=4.37) and 75.0 points (66–84), respectively, in 2014, and were 76.9 points (SD=6.12) and 76.5 points (66–91), respectively, in 2015. Over the 2 years, their scores ranged from 66 to 91 points (Fig. 1).

Looking at the change in empathy scores by gender, there were no significant changes in the total empathy score and the three sub-categories for both male and female students when they entered their fourth academic year. The total score and the scores in the three subcategories increased, but not to a statistically significant extent, as the students entered their fourth academic year (Table 3).

4. Differences in empathy scores by vocational aptitude type, and changes in empathy scores as grades change

Through examining the empathy scores by vocational aptitude type, it was found that the median scores of third-year students of realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional types were 77.5 points (67–108), 76.0 points (67–108), 73.0 points (66–81), 75.0 points (68–91), 80.0 points (57–103), and 77.0 points (68–86), respectively. The median scores of fourth-year students were 78.0 points (67–105), 77.0 points (67–92), 79.0 points (68–91), 78.0 points (66–84), 76.0 points (73–80), and, 80.0 points (71–99), respectively. In attempting to verify the differences in empathy scores by vocational aptitude, there was no significant difference in total empathy scores found among the six types of vocational aptitude in the third and the fourth year (Table 3).

Through verifying the change of empathy scores according to the year by vocational aptitude type, it was found that the total empathy scores of third-year students of artistic type increased significantly when they entered their fourth year. In terms of the sub-domain scores, for students of realistic type, their scores decreased significantly in the “perspective taking” domain, but they showed higher scores in the domain of “compassionate care” as they entered their fourth academic year (Table 3).

Through examining the difference in empathy scores between person-oriented and object-oriented students, it was found that there was no significant difference in the total empathy score and the scores in the three subcategories between the two groups in the third academic year. However, in the fourth year, there was no difference in the total score between the two groups, but there were differences in the three sub-categories (Table 3).

Through examining the change of empathy scores between person-oriented and object-oriented students, it was found that the mean empathy score for person-oriented third-year students was 75.8 points (SD=7.99) while the median was 74.5 points (57–103). In the fourth year, the mean was 77.6 points (SD=5.03) and the median was 78.0 points (66–91), a significant increase. For object-oriented students, the mean empathy score of third-year students was 78.8 points (SD= 8.65) and the median was 77.0 points (67–108). When they entered their fourth year, the mean was 79.0 points (SD=8.17) and the median was 78.0 points (67–105), indicating no significant increase. However, the empathy scores in the “compassionate care” area increased significantly as third-year students entered their fourth year (Table 3).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the changes in the empathy scores of seniors who experienced clerkship at medical school. The findings of this study are as follows. First, based on 140 points, the empathy score of third-year students (86.2 points) at KNUSOM and the score (87.3 points) when they entered their fourth academic year were lower than those of the students in their clinical grade (third or fifth year) and last grade (fourth or sixth year) in Korea [9], the United States [16], China [15], Japan [29], Bangladesh [11], and Brazil [8]. Furthermore, the students’ empathy score at KNUSOM was even lower than that of physicians working at a university hospital in Korea [17].

The reason for this may be attributed to the influence of Asian culture, in which the doctor-patient relationship is more patriarchal and authoritarian compared to the West, or due to personal cultural differences [24]. The lower empathy scores of KNUSOM compared to other schools in Korea may be attributed to the characteristics of local culture. Another possible explanation is that courses related to the doctor-patient relationship and empathy are arranged in the lower grades rather than in higher grades in the KNUSOM curriculum. KNUSOM is applying their 2020 curriculum, in which courses related to the medical humanities are evenly distributed throughout all of the six academic years and are organically linked to each other. However, the new curriculum is being applied from the lower grades, so the participants in this study still followed the old curriculum. Once the new curriculum is applied to all of the students in every academic year, students will be able to take courses related to the doctor-patient relationship systematically and continuously, which will result in improvements in empathic ability among KNUSOM students.

Second, the results of this study show that the empathy score of third-year students increased slightly—though not to a statistically significant extent—after experiencing clinical clerkship in the fourth year, which contradicts the findings of some studies, which suggested a decrease in the final academic year [11,12]. On the other hand, the results of this study are consistent with multiple studies suggesting that the empathy scores do not decrease in the final year, but rather increase, even if the difference is not statistically significant [6,8,15,24]. Regarding the reason for the increase of empathy in the final year, one study suggested that this could be attributed to the psychiatric clinical practice conducted in the third year having a positive effect on empathy, as well as the fact that the empathy test was performed in the middle of the fourth year, not at the end of the fourth year [24]. Other studies suggested that early exposure to clinical training provided more opportunities to develop empathy throughout each year, as more opportunities to meet actual patients were available from the lower years [8,15]. There is another study suggesting a reason why empathy levels of higher-grade students do not decrease. This qualitative analysis of a “hidden curriculum” that affected students’ empathy discerned an identity developmental trajectory in early clerkship in which students began with feelings of excitement, switched quickly to “shock and awe,” entered into “survival mode” and then reached a stage of “recovery” [13]. According to their analysis, medical students’ empathy levels decreased temporarily in early clerkship when they initially had difficulty adapting to the hospital environment. However, their empathy levels recovered soon after they became accustomed to the hospital environment.

The author assumes that the slight increase—though not statistically significant—of empathy scores in the final year compared to the third year was attributed to the positive effect of measuring empathy in the first half of the fourth year. Clinical practice is also conducted in the second half of the fourth year at KNUSOM, but the students may not be able to concentrate on clinical practice because they have to take the clinical skills assessment in the Korean Medical Licensing Examination and prepare for the written examination. On the other hand, they have more intensive practice opportunities such as student internships and elective practice courses in the first half of the fourth year, where they experience more clinical practice with their clinical supervisors and meet more patients. Therefore, the author interprets that conducting the empathy test early in the fourth year may have had a positive effect on maintaining the level of empathy they acquired in the third year.

Third, this study found a difference in empathy scores between male and female students in 2004. Unusually, however, the male students had a higher mean score compared with the female students. This finding is in contrast with the general finding that there was no gender difference [7,24] and that female students have higher empathy scores [2,9,11,12,15,16,29]. However, the interesting fact about the results of this study is that the male students’ score distribution was wider than that of female students, and that the female students had similar scores. The difference between the lowest and highest student scores over the 2 years was 51 points among male students, but 25 points among female students. The author interprets that the large deviation in male students’ empathy scores resulted in their empathy scores being higher than those of female students. Considering the fact that 98.4% of female students and 88.0% of male students had scores in the range of 60–89 points, the mean score of male students may have varied due to the number of male students outside this range. There were no female students with scores below 59 points or higher than 100 points, while six male students had scores below 59 points or higher than 100 points. Therefore, the author considers that the mean score of male students was higher than that of female students due to the higher variability among the male students. The mean score of the male students was assessed to be greatly influenced by the extremely high or extremely low scores.

The wider distribution of scores among male students compared to female students was also found in other studies in Korea [9,24], China [15], Japan [29], Bangladesh [11], the United Stabes [16], and the United Kingdom [12]. Similarly, the distribution of male students’ scores was wider than that of female students, regardless of the difference between male and female students in median and mean empathy scores. The findings of these studies showed that male students generally had larger individual differences in empathy compared to female students.

Fourth, although post-testing was meaningless because the difference in empathy between the 6 Holland vocational aptitude groups was not significant, this study performed Mann-Whitney U-tests between the two types within the vocational aptitude groups considering Type II errors and the exploratory aspects of this study. As a result, in 2014, there were no differences in the total and sub-category scores between the types in the two groups. In 2015, there was no difference in total scores, but there was a group with different empathy scores in the sub-categories between the two types. In the perspective taking area, enterprising types scored significantly higher than realistic and investigate types. In the compassionate care area, enterprising types scored significantly lower than realistic, investigative, and conventional types. Realistic types scored higher than artistic types. In the emotional detachment area, realistic types scored significantly higher than investigate and enterprising types.

Fifth, the finding that the empathy scores of third-year students who preferred person-oriented specialties were higher compared to those who preferred object-based specialties as they entered their fourth year was consistent with the results of another study [19], which found that students who chose person-oriented clinical departments for their career showed higher empathy scores than students who chose technology-based clinical departments. In that study [19], the students were asked directly about their future medical specialties, whereas in this study, students’ preferences were classified into two types using the vocational aptitude test. In this study, the author analyzes that the empathy scores of students who preferred person-oriented specialties increased as they entered their fourth academic year because realistic types were classified as person-oriented types. According to Holland’s vocational preference classification, realistic students showed a significant score increase in the “compassionate care” area over the academic year, which may have had a significant influence.

The limitation of this study is that it is difficult to generalize its results because the survey was performed at one medical school in Korea. However, other medical schools should refer to this study, considering that medical schools have similar curriculums and that the results of this study are similar to those of other Korean studies that have measured students’ empathy levels. In addition, this study cannot completely exclude the possibility that the respondents’ tendency to give positive answers was reflected in the survey because the survey is not an objective measurement tool but a self-reported method of measuring empathy. Also, it should be considered that there is a possibility that students’ responses can be influenced by cultural factors. In addition, although the ideal approach is to use a nonanonymous survey to analyze and match the data to examine the changes in empathy scores, the author was unable to match the data of the 3rd and 4th grade students due to using anonymous questionnaires because the participants were reluctant to let their psychological test results be known. Therefore, the data for each grade were viewed as independent samples, which may have reduced the power of the test.

Nevertheless, this study is significant because it marks almost the only example of male students showing higher empathy scores than female students. This is also the first case in Korea to analyze the relationship between job preference trends and empathy among students.

Further studies should investigate the changes in empathy scores with data that is matched according to each grade and investigate whether the higher empathy scores of male students compared to female students are specific to a single medical school or if it is a generational trend. Most of the previous studies only verified the difference in scores between males and females, but hardly analyzed the aspects of the distribution of scores by gender in detail. Some studies have suggested that this difference is due to evolutionary aspects or social learning [16], and analyzed the gender difference from a neuroscience perspective [30], suggesting that the behavior of individual mirror neurons leads to differences in empathy. However, further research is required to examine whether these differences are attributed to biological gender differences, specialties, or individual differences. In addition, if there is a large individual difference in empathy, further research should be conducted to develop teaching strategies on how to reflect individual differences in educational programs to foster students with empathy.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

SY contributed in the design, data collection, analysis, writing, and editing.