Medical students’ self-directed learning skills during online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic in a Korean medical school

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study examined medical students’ self-directed learning skills in online learning contexts, and whether there were any differences among the student groups (from pre-medical program year 1 to medical program year 2) amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. It also explored the components of self-directed learning skills influencing their perceived learnring performance and satisfaction in online learning contexts.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional survey design and convenience sampling. It was conducted in a Korean medical school, which delivered all courses online because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The self-directed learning skill survey, which included student satisfaction and perceived learning performance items, was disseminated over two weeks through email to the participants. The collected data were analyzed through descriptive statistics, analysis of variance, and multiple regressions.

Results

The survey response rate was 70% (140/200). The overall mean of self-directed learning skills was 3.85. Students in medical year 2 showed the highest score (4.15), while students in medical year 1 showed the lowest score (3.69). The learning plan category score (3.74) was the lowest among the three categories. The pre-medical program year 1 students showed the lowest score in the perceived learning performance (3.16), and only the learning plan category impacted student satisfaction (t=2.605, p=0.041) and perceived learning performance (t=3.022, p=0.003).

Conclusion

When designing online learning environments, it is imperative to provide features to help students set learning goals and search diverse online learning resources. In addition, it is an effective strategy to provide the students in medical program year 1 with self-directed learning skills training or support for successful online learning.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has changed our society in many ways, and the medical education sector is not an exception. Medical schools worldwide have switched to online courses, and this sudden transition draws attention to medical students’ self-directed learning skills since they are vital factors for successful online learning [1,2].

Online learning can prove to be a challenge for some students [3]. It provides students with time flexibility and convenient places for learning. However, the asynchronous and virtual nature of online learning expects learners to take responsibility for their learning, that is, to assume greater control of planning, monitoring, and managing their learning processes [4,5]. Previous studies have reported obstacles to successful online learning, self-discipline, self-management, taking initiative, time management, organizational skills, and cognitive strategies [6]. Correspondingly, the lack of self-directed learning skills is one of the greatest barriers to successful online learning [3].

Self-directed learning is the learning process where an individual takes the initiative, with or without others’ support, to determine learning needs, formulate learning goals, identify learning resources, choose and implement appropriate learning strategies, and evaluate learning outcomes [5]. In medical education literature, self-directed learning has been highlighted as a life-long learning skill [7-16] and many of these studies have measured medical students’ self-directed learning readiness in classroom contexts. Self-directed learning readiness is defined as the attitudes, values, abilities, and personal characteristics that an individual possesses, which support self-directed learning [7,8]. Some previous studies reported significant drops or no differences in the self-directed learning readiness across academic years at medical school [12-14]. Meanwhile, some other studies reported that self-directed learning readiness increased after implementing student-centered learning activities such as problem-based learning (PBL), flipped learning, or additional group activities [9-11].

Instead of measuring students’ self-directed learning readiness based on students’ personal attributes, self-directed learning skills can be measured with learning behaviors or attitudes associated with the learning process, including planning, implementation, and evaluation [5,17,18]. If self-directed learning skills are measured by focusing on the learning processes, it is easier for medical educators to promote and encourage students’ self-directed learning skills. However, extant studies have hardly focused on the learning process to measure self-directed learning skills in medical education contexts.

Furthermore, most of the extant studies regarding self-directed learning skills in medical education were conducted in face-to-face contexts. Knowledge about students’ self-directed learning skills online can help develop online education in a useful direction [19]. The flexible structure of online learning environments requires students to exert more control over their own learning [20]. A well-designed online learning environment can provide a conductive context to help students to train and exert self-directed learning skills [20]. To develop such an environment, understanding medical students’ self-directed learning skills online is a prerequisite, but there is very limited information about this aspect. Considering that online learning has continuously become one of the most powerful learning mediums in medical education settings, it is imperative to investigate this critical issue.

In addition, there is limited knowledge about the effects of students’ self-directed learning on learning outcomes in online learning contexts. Some studies reported that self-directed learning has a positive relationship with learning outcomes [21,22], but some others revealed that self-directed learning is not a strong indicator of successful learning outcomes in online learning contexts [23]. Additional research is needed to obtain a more complete picture to understand its effects on learning outcomes in online learning contexts.

Given this research gap, this study aimed to explore medical students’ self-directed learning skills in online learning contexts. In this study, self-directed learning skills were conceptualized as learning behaviors or attitudes associated with the learning process that includes planning, implementation, and evaluation. In addition, previous studies show conflicting results, reporting a significant drop or increase in medical students’ self-directed learning readiness across the academic years [9-14]. Thus, this study also explored whether there were differences in self-directed learning skills across the academic years in online learning contexts. Finally, it examined which components of self-directed learning skills influenced students’ perceived learning performance and satisfaction in online learning contexts as well as whether there were differences in their perceived learning performance and satisfaction among the student groups.

Methods

1. Participants and procedure

This study used a cross-sectional survey design, and the participants were drawn from convenience sampling. It was conducted in a medical school in Korea. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this medical school delivered all the courses online, normally held face-to-face, through a learning management system (LMS). All medical schools in Korea have 6-year programs, which consist of 2-year pre-medical and 4-year medical programs including 2-year clinical clerkships. Once admitted into a medical school, students progress from the 2-year pre-medical courses to the 4-year medical courses, unless they fail the course. This medical school adopted a competency-based curriculum in 2018. It implemented more student-centered learning methods, such as additional small group activities, flipped learning, PBL, and group research programs, even though most classes were taught using traditional, lecture-oriented methods in large classroom settings. During the pandemic, courses were delivered both asynchronously, with recorded lectures through the LMS, and synchronously, through Zoom. However, the main delivery method was the recorded lectures through the LMS. All other learning resources were also uploaded onto the LMS.

This study has been approved by the Dong-A Institutional Review Board (IRB no., 2-1040709-AB-N-01-202107-HR-056-02). To examine students’ self-directed learning skills, a survey was disseminated over 2 weeks through the LMS email system to all the students enrolled in the pre-medical program year 1 to the medical program year 2 (N=200) at the end of the semester. The students in the medical program year 3 and 4 were excluded as they were in their clinical rotations and hardly took courses online during the pandemic.

2. Instrument

The survey used in this study was composed of 50 items, including 45 self-directed learning skills, one perceived learning performance, one student satisfaction, and three background information items. The survey to measure medical students’ perceptions of their self-directed learning skills was developed by Lee et al. [18] and presented on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often), asking “To what extent do you indulge in this behavior in online learning contexts?” The perceived learning performance item (overall, online classes were successful and I learned a lot) and student satisfaction item (overall, I am satisfied with the online learning experience) were also presented on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Lee et al. [18] developed the self-directed learning skill scale to measure learning behaviors or attitudes associated with self-directed learning focusing on learning processes, including planning, implementation, and evaluation. It consists of three categories and eight sub-categories. The learning plan includes three sub-categories (diagnosing learning desire, setting learning goals, and identifying learning resources). Meanwhile, the learning implementation includes three sub-categories (self-management, learning strategies, and learning persistence), and the learning evaluation includes two sub-categories (effort attribution to results and self-reflection). The number of items in each sub-category was 5, except for diagnosing learning desire, which had 10 items. Among the 45 items, one item was eliminated from the learning persistence sub-category owing to low internal consistency. Consequently, 49 items in total were analyzed.

3. Data analysis

The internal consistency of the self-directed learning skill scale was first checked. The Cronbach’s α values for the whole scale, three categories and sub-categories were all above the acceptable level (0.70). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the means and standard deviations of all variables. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare differences in the self-directed learning skills, perceived learning performance and student satisfaction among the four groups (pre-medical program year 1 [pre-med 1], pre-medical program year 2 [pre-med 2], medical program year 1 [med 1], and medical program year 2 [med 2]) and the Scheffe test was used for the post hoc analyses. Lastly, multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of each self-directed learning skill category on perceived learning performance and student satisfaction. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) and the statistical significance level in this study was p<0.05.

Results

1. Internal consistency

The Cronbach’s α for the whole scale in this study was 0.95. The Cronbach’s α for three categories were 0.85 (learning plan), 0.87 (learning implementation), and 0.84 (learning evaluation), while for the sub-categories, it was 0.85 (diagnosing learning desire), 0.81 (setting leaning goals), 0.84 (identifying learning resources), 0.70 (self-management), 0.73 (leaning strategies), 0.73 (learning persistence), 0.82 (effort attribution to results), and 0.83 (self-reflection).

2. Participants’ characteristics and descriptive statistics

Among 200 students in total, 140 students (70%) responded to the survey, of which 49 (35%) were female and 91 (65%) were male and their ages ranged from 20 to 31, with the mean age being 22.80. Among the subjects, 33 were in pre-med 1, and 30 in pre-med 2, 42 in med 1, and 35 in med 2. The mean values and standard deviations of self-regulated learning skills, their categories and sub-categories, student satisfaction, and perceived learning performance were demonstrated in Table 1.

3. ANOVA results

To investigate the differences among groups, ANOVA was conducted. Significant differences were found in self-regulated learning skills (F [3, 136]=5.54, p<0.00, η2 =0.11) and perceived student performance (F [3, 136]=5.21, p<0.00, η2=0.10), while no significant difference was found in student satisfaction (F [3, 136]=1.58, p=0.20, η2 =0.03). According to the Scheffe test, significant differences in self-regulated learning skills were determined between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups. Significant differences in perceived student performance were found between the pre-med 1 and med 1 groups, and between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups.

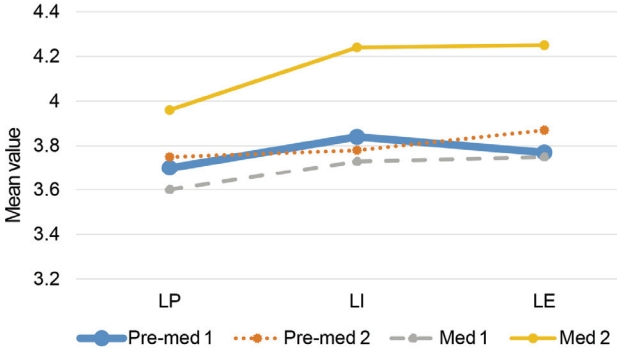

Fig. 1 demonstrate the mean values of the categories and sub-categories of self-directed learning skills by each group. Regarding the categories, learning implementation (F [3, 136]=7.89, p<0.00, η2=0.15) and learning evaluation (F [3, 136]=5.79, p<0.00, η2=0.11) showed significant differences, while learning plan (F [3, 136]=2.45, p=0.07, η2 =0.05) showed no significant difference among the groups. According to the Scheffe test, significant differences in learning implementation were found between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups, between the pre-med 2 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups. Significant differences in learning evaluation were found between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups.

Means of the Categories by Each Group

LP: Learning plan, LI: Learning implementation, LE: Learning evaluation, Pre-med 1: Pre-medical program year 1, Pre-med 2: Pre-medical program year 2, Med 1: Medical program year 1, Med 2: Medical program year 2.

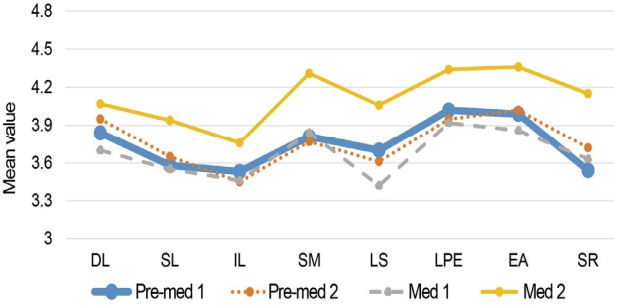

Regarding the sub-categories, diagnosing learning desire (F [3, 136]=2.69, p=0.049, η2=0.06), self-management (F [3, 136]=5.47, p<0.00, η2=0.11), learning strategies, (F [3, 136]=6.92, p<0.00, η2=0.13), learning persistence (F [3, 136]=4.10, p<0.01, η2=0.08), effort attribution to results (F [3, 136]=4.62, p<0.00, η2=0.09), and self-reflection (F [3, 136]=5.02, p<0.00, η2=0.10) showed significant differences, while setting lesson goals (F [3, 136]=1.73, p= 0.16, η2=0.04) and identifying learning resources (F [3, 136]=1.12, p=0.35, η2=0.02) showed no significant difference among the groups. The Scheffe test found significant differences in diagnosing learning desire between the med 1 and med 2 groups, and in self- management between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups, between the pre-med 2 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups. Significant differences in learning strategies were determined between the pre-med 2 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups, and in learning persistence between the med 1 and med 2 groups. Significant differences in efforts attribution to results were also found between the med 1 and med 2 groups, and in self-reflection between the pre-med 1 and med 2 groups, and between the med 1 and med 2 groups.

Means of the Sub-categories by Each Group

DL: Diagnosing learning desire, SL: Setting learning goals, IL: Identifying learning resources, SM: Self-management, LS: Learning strategies, LPE: Learning persistence, EA: Effort attribution to results, SR: Self-reflection, Pre-med 1: Pre-medical program year 1, Pre-med 2: Pre-medical program year 2, Med 1: Medical program year 1, Med 2: Medical program year 2.

4. Multiple regression results

To explore the effects of each self-directed learning skill categories on perceived learning performance and satisfaction, first, the assumptions of normality, independence of the residues (student satisfaction: Durbin- Watson [D.W.] test=1.946 and perceived learning performance: D.W.=1.912), and multicollinearity (learning plan: variance inflation factor [VIF]=2.97; learning implementation: VIF=3.09; learning evaluation: VIF=3.70) were verified and no violation was found. The multiple regression model for student satisfaction was significant (F [3, 136]=10.081, p<0.000) and explained 18.2% of the variance in student satisfaction (R2=0.182, adjusted R2=0.164)). In this model, only one variable, the learning plan was a significant predictor (t=2.065, p=0.041) as demonstrated in Table 2. The multiple regression model for perceived learning performance was also significant (F [3, 136]=14.320, p<0.000) and explained 24% of the variance in perceived student performance (R2=0.240, adjusted R2=0.223). In this model, likewise, one variable, the learning plan was a significant predictor.

Discussion

This study explored medical students’ self-directed learning skills in online learning contexts and the differences in the self-directed learning skills, perceived learning performance, and student satisfaction among the student groups from the pre-medical program year 1 to the medical program year 2. It also explored which components of self-directed learning skills influence students’ perceived learning performance and satisfaction in online learning contexts. According to the results, the overall mean score of self-directed learning skills was 3.85, which was a little bit high. This score is marginally higher than 3.67 in the study of Premkumar et al. [13], but lower than 3.98 in the study of Premkumar et al. [12]. These authors used the self-directed learning readiness scale to measure medical students’ self-directed learning skills in classroom contexts, but the level of students’ self-directed learning in all three studies, including this present study, seems similar.

The learning evaluation category and its sub-category, effort attribution to results, demonstrated the highest scores. In addition, the sub-category, learning persistence, also showed the highest score among the sub-categories. The medical students showed the relative confidence to exert those skills in online learning contexts. On the other hand, the learning plan category and its sub-categories, setting learning goals and identifying learning resources, demonstrated the lowest scores and did not show a significant difference across the school year, while all the other categories and subcategories showed a significant difference. These results indicated that when designing online learning environments, it is imperative to provide features to help students set learning goals or search for diverse online learning resources. This result is in line with the studies of van Houten-Schat et al. [24], Kim et al. [3], and George et al. [25] indicating the goal-setting skill as a positive influential factor for self-directed learning. In addition, a study by Barton et al. [26] investigated medical students’ learning resources used for self-directed learning before and during the pandemic and found that medical students’ independent study time and use of resources (for example, website) significantly increased. However, the most common resource was from the class, and accessibility was the most influential factor to guide students’ digital resource choice. These studies seem to provide practical implications. Specifically, adopting a personalized learning system through e-portfolio, or dashboard design to enable students to set individual learning goals and providing guidance on locating and evaluating learning resources can be effective strategies to improve students’ self-directed learning skills in online learning contexts.

The med 2 students showed a significantly higher score compared with the pre-med 1 students and the self-directed learning skill scores in general showed a steady increase, except for med 1 students. These results showed a different result from the ones in the study of Premkumar et al. [12,13]. In their study, the medical students’ self-directed learning readiness decreased as students progressed through the medical school. However, the studies of Kim and Yang [11] and Kidane et al. [9] showed that the self-directed learning readiness scores increased following the introduction of the criterion-referenced grading system with increased group activities [11] or a hybrid program combining traditional teaching method and PBL [12]. Although these studies used a different tool to measure self-directed learning in different contexts (face-to-face contexts) from this study, these results seem to indicate the importance of increased learning activities that promote self-directed learning skills. As mentioned earlier, the medical school where this study was conducted started a competency-based curriculum from 2018 and employed more student-centered learning methods, which seemed to contribute toward stimulating students’ self-directed learning skills. Furthermore, during the pandemic, online learning experiences also seemed to provide students conductive contexts to execute and train self-directed learning skills. However, additional research is needed to understand this issue further.

The med 1 students showed the lowest score among the four groups in most of the categories and sub-categories. One of the possible explanations for the decrease in first-year students’ self-directed learning skills is their lack of subject knowledge and limited mental capacity [27,28]. Francom [27] argued that a certain degree of knowledge is necessary for learners to assume responsibility for learning. In the first-year medical program, the students have very little foundational knowledge in medicine. Accordingly, the novices who lack subject knowledge may not have the mental capacity for processes related to self-directed learning skills unlike experts who enable to free up their mental capacity for those process, considering the limited mental capacity of human beings (see cognitive load theory) [28]. Therefore, with increasing workload in the first-year medical program, it is an effective strategy to provide, particularly, med-1 students with self-directed learning skills training or support for successful online learning.

The pre-med 1 students showed the lowest score in perceived learning performance and student satisfaction, although there was no significant difference in student satisfaction. This underscored pre-med 1 students’ frustration with online learning contexts. The fact that it was their first semester in medical school and the courses were totally delivered online could be a challenge to them. If this current online learning situation continues, more effort should be provided to assist students in pre-med 1 in learning online.

Among the three categories, only the learning plan had an impact on student satisfaction and perceived performance. This result is in line with previous research, which reported that self-directed learning skills have a positive impact on online learning outcomes [19]. In addition, a study by Zheng and Zhang [22] reported that after flipped learning, self-directed learning skills, particularly, peer-learning and help-seeking, were positively related to medical students’ academic performance, while Kidane et al. [9] reported that there is no significant relationship between academic performance and self-directed learning skills after PBL. However, both the studies were conducted in classroom settings. More research is necessary to understand the impact of self-directed learning skills and their components on learning outcomes in online learning contexts.

The results of this study provide insights for designing support strategies for developing students’ self-directed learning skills online. Medical educators should not assume that medical students possess all the necessary skills related to self-directed learning without training [29]. Medical education will increasingly be conducted online in the future, so educators need to take responsibility to provide structure and guidance that will encourage and support medical students’ self-directed learning in online learning contexts.

This study has limitations. Although a substantial number of students participated in the study, this study was conducted in a single university, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies with a larger group of students from diverse backgrounds is necessary to further support its findings. Longitudinal research to follow a cohort is also necessary to verify the findings in this study. In addition, this study relied on self-reported data. Although self-reports are commonly used in self-regulated learning studies and the survey was conducted anonymously, there is still the possibility that the students’ responses were influenced by a social desirability bias. Future research incorporating other objective data, such as their online learning behaviors, is necessary to back up the findings of this study.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

Funding

This work was supported by the Dong-A University research fund.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

All work was done by Jihyun Si.