Online continuing medical education in Mongolia: needs assessment

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Due to the shortage in the healthcare workforce, insufficient qualifications, a lack of infrastructure and limited resources in Mongolia, it is not always possible for healthcare workers in rural areas who wish to attend continuous training and retraining courses to do so. However, in order to provide high-quality care, the demand for distance learning and the upgrading of knowledge and practice of many medical topics (especially related to morbidity and mortality) are necessary for the rural population. This study aimed to assess the needs of e-learning medical education, of graduates in Mongolia.

Methods

A cross-sectional research design was implemented. We collected data from 1,221 healthcare professionals (nursing professionals, physicians, midwives, and feldshers) who were randomly selected from 69 government hospitals in Mongolia. Data were collected using self-assessment questionnaires which captured the needs assessment in a survey for online continuous medical education in Mongolia. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and Kruskal-Wallis statistical test.

Results

Ninety percent of the respondents reported that they plan on attending online continuous medical education with the most preferred specialty area being emergency medicine. Results using the Kruskal-Wallis statistical technique suggested the preferred specialty area, educational content, appropriate time schedule, available devices, and tools were statistically significant and were different between the nursing professionals, physicians, midwives, and feldshers (p<0.05).

Conclusion

Findings provide important evidence for the implementation of measures and strategies which can assist healthcare professionals in low and middle-income areas/countries to constructively address their need for enhanced knowledge and practice through distance learning.

Introduction

Introducing modern technologies into the health system can improve the quality of healthcare in developing countries [1,2]. It is essential to develop e-learning for medical graduate education in low and middle-income countries to address the critical health worker shortages, limited health care budgets [2], an insufficient number of qualified healthcare workers (HCWs) [3], and a lack of infrastructure and resources [4,5]. E-learning interventions for medical education are beneficial in minimizing the issue of distance in rural communities, where it is currently difficult to access up-to-date information for medical education, and in the provision of high-quality care, especially in low-resource settings [6,7].

In Mongolia, as in other countries, online or distance learning is not a new concept; however, transitioning from the traditional classroom setting to online learning still has many challenges such as slow clinical acceptance, availability of the required information and communications technology infrastructure (e.g., internet connection, lack of electricity, and adequate communication media) especially in rural areas [8]. The first distance learning program in Mongolia was implemented in the field of medical education in 2003 with the Online Medical Diagnosis Project. The Postgraduate Training Institute, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (MNUMS) began the program in order to enhance distance education for rural medical workers who needed to upgrade their knowledge and practice on a variety of topics [9]. In 2007, telemedicine and the Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment system for distance learning [10], were expanded and developed. In 2015, the e-Learning Center and the International Cyber University were established at MNUMS to provide accessible online training for people around the nation [11].

Today, the healthcare system in Mongolia struggles with medical worker shortages, and there is a HCWs to population ratio of 171.4/10,000 [12]; this is very low compared with some Asian countries (e.g., Japan, Australia, and New Zealand) [13]. There are insufficient numbers of qualified healthcare providers, especially in rural areas. The MNUMS is the only national university accredited for health professions education and biomedical research. It was established in 1942, and has trained more than 90% of the health professionals in the country. It includes the School of Medicine, the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, the School of Dentistry, the School of Nursing, and the School of Public Health, and has approximately 800 faculty members and 10,000 undergraduate and graduate students [14]. The School of Nursing provides for the training of nurses, midwives, and feldsher in Mongolia at the two levels of diploma and bachelor’s degrees. All medical graduates must pass the licensing exam and obtain a 5-year license and be eligible to work in both public and private health facilities. In order to extend one’s license, health professionals must take the licensing exam again or collect sufficient continuing education credits within 5 years [15]. Health workers in Mongolia are licensed with licensure maintenance contingencies covering regular participation in accredited continuing medical education (CME) activities. Licensing directly influences the quality of patient care and patient safety and is essential for improving the skills and performance of the graduates [16].

Due to the size and low population density of Mongolia, e-learning initiatives can be a cost-effective method of delivering continuous higher education [17]. The nation’s rural medical services are underdeveloped, and the healthcare infrastructure is especially inadequate outside the cities, where rural communities have no access to the quality of health care provided to the urban population. Delivery of health services to rural patients is difficult due to low population density, severe climate events and poor transportation and communication facilities. Medical education topics in distance-based lectures should be prioritized and based on morbidity and mortality in the rural population. It is not always possible for healthcare professionals from rural areas to attend training or retraining courses as it would require them to leave their posts at local hospitals, causing disruptions to areas already struggling to meet healthcare needs [9]. Therefore, this study aimed to discern a needs assessment and development for e-learning medical education among graduates in Mongolia.

Methods

1. Design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study investigating the needs assessment of online continuing medical education among graduates in Mongolia.

2. Population and sample

Our calculation yielded a sample size of 1,275 healthcare professionals recruited from 69 hospitals owned and operated by the government of Mongolia. The proportional stratified random sampling technique was applied to adjust for the number of healthcare professionals in each hospital.

3. Eligibility criteria

Healthcare professionals were eligible to participate in the study if: (1) they had earned a degree and graduated from MNUMS and medical colleges, (2) they were actively employed by the government hospital system, and (3) they were willing to participate in our study. Healthcare professionals who had participated in the pre-testing stage of the study were excluded to reduce the likelihood of information bias.

4. Research instrument

The research instrument was based on an overall perspective of distance learning, first proposed by Amarsaikhan et al. [9] in 2007 in Mongolia. The modified items and components of the questionnaire were based on the documents related to online learning and professional development found in MNUMS, Mongolia and previously implemented for online a learning needs assessment project published by the World Health Organization, Center for Health Development, and MNUMS, Mongolia. This step was followed by drafting and scaling a total of 83 items (16 items were related to demographic questionnaires, four additional items were to be answered if the doctor involved was a professional, 15 items were on the use of digital technology, 14 items covered learning needs, 11 items were on online learning knowledge and use, and 23 items were related to online learning needs assessment) in Mongolian language. Cronbach’s α coefficient of internal consistency for reliability at pre- and post-testing was calculated at 0.85.

5. Data collection

This research was approved by the Bio-Medical Research Ethics Committee of Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (approval no., 2020/03-1) and by the participating hospitals in Mongolia. The director of each participating hospital gave his/her approval before implementing the study. The research instrument was distributed to the 1,275 healthcare professionals who had consented to participate in our study. At each hospital, one of the members of the research team and the designated research assistant assumed responsibility for the distribution of the research instrument and collection of data. The questionnaire was distributed and returned manually and study participants completed the research instruments at a time convenient for them and returned their anonymously completed instruments to the research assistant. Data were collected from December 2019 through October 2020.

6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the study participants and the online learning needs assessment. Study participants were categorized by their professional title, and differences in frequency distributions of the measured online learning needs assessments were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis statistical test of significance. All statistics tested were two-sided and analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

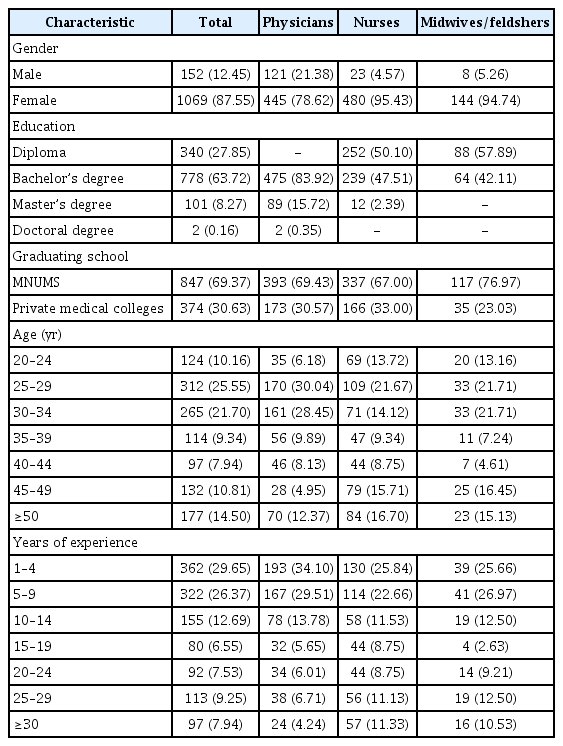

Of the total 1,275 research instruments distributed, 1,221 (95.76%) were completed and returned by healthcare professionals. Most of the respondents (47.25%, n=577) were between the ages of 25 and 34 years. About 63.72% (n=778) of them had completed their baccalaureate academic training in medical sciences. Stratification of the study participants by their professions categorized 46.30% (n=566) as physicians and 41.20% (n=503) as nursing professionals, while the remaining 12.50% (n=152) were midwives/feldshers (Table 1).

The majority of respondents (91%) reported an intention to attend online continuous medical education and the most preferred specialty area was emergency medicine (43.57%). More than half of the respondents (57.42%) wanted an online course schedule of 7 days to 3 months in length. Results from the Kruskal-Wallis statistical technique suggested the preferred specialty area, educational content, appropriate course length, devices and tools were statistically significantly different between the nursing professionals, physicians, and midwives (p<0.05). While the preferred teaching method and class type were not statistically significant among healthcare professionals (p>0.05) (Table 2).

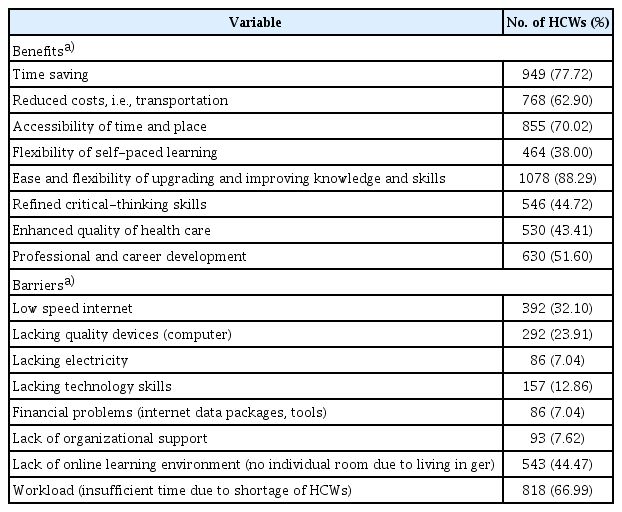

Regarding benefits of and barriers to distance learning, HCWs reported having multiple advantages including time-saving (77.72%), reduced costs, i.e., transportation (62.90%), accessibility of time and place (70.02%), flexibility to upgrade knowledge and skills (88.29%), refined critical-thinking skills (44.72), enhanced quality of health care (43.41%), and professional and career development (51.60%). Workload (66.99%), lack of online learning environment (44.47%), internet streaming quality and coverage (32.10%), and lack of quality devices (e.g., computers) (23.91%) were the main challenges reported by HCWs. A summary of reported benefits and barriers is summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

This study was based on data obtained from a questionnaire, and the wide geographical distribution of the participants demonstrates the considerable demand for continuing education via high-quality distance learning for inexperienced physicians, nurses, and midwives. The findings of this study indicated that the majority of respondents reported an intention to attend online continuous medical education. Online distance learning may be considered a relevant tool for eliminating geographical barriers to knowledge and the nationwide distribution of knowledge. Continuing education in emergency medicine demonstrated the most preferred specialty area among the HCWs. Basic emergency procedures (wound care, foreign body removal, oxygen application) were common in online learning courses, but advanced procedures (advanced cardiac life support, airway management, mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy) were rarely available. In rural areas and primary-level hospitals in Mongolia, better training for staff in the area of emergency/critical care skills is essential for overall improved healthcare [18]. Developing e-learning for medical graduate education in low and middle-income countries is necessary to address critical health worker shortages, limited health care budgets, the insufficient number of qualified health workers, and the lack of infrastructure and resources [6]. More interesting they were in different places in their clinical education and had different learning needs among healthcare professionals. This may explain why the online continuing education address differences between nurses, midwives, and physicians in the clinical areas of confidence and learning needs. Our finding is consistent with the previous study by Shaw-Battista et al. [19] in 2015, which found that the diversity of participants was also sometimes perceived to be challenging, as indicated different learning needs.

After completing an online continuous medical education program, barriers to education remained, especially related to workload, lack of online learning environment, low-speed internet, lack of electricity, and use of a computer and devices. Today, the healthcare system in Mongolia struggles with medical worker shortages and an insufficient number of qualified healthcare providers, especially in rural areas [12]. Medical worker shortages are a critical obstacle to participation in CME and retraining courses and the development of better healthcare. In addition, participants perceived the lack of an online learning environment as a major challenge. Rural residents frequently live in a ger, a traditional Mongolian one-room tent. There are no individual learning rooms as all family members live in a ger together, which presents difficulties for online learning. Another common barrier to e-learning is the lack of infrastructure, technology, internet access, and the poor quality of internet service in rural areas in this study which supported by previous studies [1,20]. The key barriers which affect the development and implementation of online learning in medical education include time constraints, poor technical skills, inadequate infrastructure, and the absence of institutional strategies [21].

HCWs reported multiple advantages to online learning in this study including time-saving, reduced costs, i.e., transportation, accessibility of time and place, and flexibility in self-paced learning. As traditional approaches in medical education face more and more challenges because of the increase in clinical demands and reduction in available time, e-learning provides easier and more effective access to a wider variety and greater quantity of information [1]. Online learning interventions for medical education could be of great benefit to minimize the problem of accessing up-to-date information due to distance in rural communities in Mongolia. Delivering continuous and higher education via e-learning initiatives can be cost-effective in Mongolia due to the vast size and sparse population [17]. Moreover, previous studies suggested there was no need for time-consuming and cost-intensive travel to continuous education and retraining courses for the healthcare workforce [22].

1. Limitation

The main limitations of our study were that the cross-sectional design did not permit us to adequately discern the reason for the observed online medical education needs among the healthcare providers. Additionally, we relied on self-reported data, which meant that the more profound learning needs of respondents in our study were not identified. Future longitudinal research should be implemented to clarify the learning needs and changes in barriers of effective long-term strategies.

2. Implications

A careful needs assessment, is an important first step in planning education for any health professional. If the learners are well aware of the normative needs and have had their learning needs identified, then the educator should focus on the learners perceived or expressed needs. Learning needs assessments are often conducted to identify deficiencies in knowledge, skill, behavior, or attitude in current teaching practices as well as to anticipate deficiencies based on expected changes in health care needs [23]. Needs assessment is utilized by public healthcare, academic authorities, and medical educators to develop curriculum for training programs. The teaching must therefore be relevant and applicable and bring about a positive change in patient care [24].

This paper provides a descriptive overview of the online medical education needs assessment and discusses opportunities and challenges of online medical education implementation, focusing on rural areas. Online learning interventions for medical education could be of great benefit for bridging deficiencies in accessing up-to-date information and high-quality care and medical information for rural areas. However, administrative and technological challenges were overcome in designing and executing a novel course for varied learners [19]. Policymakers, administrators, and educators need to work in tandem to reach a consensus for developing strategies which will overcome those barriers that best promote healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practice through distance learning.

3. Conclusion

E-learning interventions for medical education could be of great benefit for distance learning in rural areas needing access to up-to-date information on medical education and the provision of high-quality care. Findings provide important evidence to aid in implementing measures and strategies which will assist healthcare professionals in low and middle-income countries desiring to constructively address their lack of knowledge and practice through distance learning.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

Funding: No financial support was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions: All authors have involved and contributed equally to conception or design of the work, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the article, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the version to be published.