Developing a core competency model for translational medicine curriculum

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to develop a core competency model for translational medicine curriculum in the Korean graduate education context.

Methods

We invited specialists and key stakeholders to develop a consensus on a core competency model. The working group composed of 17 specialists made an initial draft of a core competency model based on the literature review. The initial draft was sent to the survey group by email to ask whether they agreed or disagreed with each core competency. The working group simplified, merged, or excluded the competencies that received less than 80% agreement among the 43 survey respondents. The working group also reorganized the order of the domains and competencies based on the survey results, and clustered the domains into four major areas.

Results

The final core competency model has four areas, 12 domains, and 34 core competencies. The major areas are theory-based problem assessment and formulation, study design and measurement, study implementation, and literature review and critique.

Conclusion

This new core competency model will provide guidance for the competency based education of translational medicine in Korea.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, the translation of basic scientific discoveries into clinical applications and public health improvements has become a major focus in biomedical research [1]. Translational medicine research fosters the multidirectional integration of basic science, clinical medicine, and population-based approach, to ultimately improve the health of the public [2]. The concept and the role of translational medicine research has been more clearly defined by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) community in recent years. The CTSA Education and Career Development Key Function Committee collaborated over several years to identify 14 thematic areas of core competencies for clinical and translational medicine research [3]. These core competencies let the directors of translational medicine degree programs to be sure that their curriculum is comprehensive and that the students achieve these competencies through their training programs [4].

However, the CTSA core competencies which were developed in the context of the United States of America cannot be directly applied to other countries throughout the world due to their different system, contexts and cultural backgrounds. In the Korean academy, core competencies for translational medicine curriculum have not yet been clearly defined. Without a clear definition, developers of translational medicine curriculum will struggle to define specific program objectives, to specify the knowledge and skills that trainees are expected to develop, to select appropriate teaching and learning methods, and to assess whether competencies are achieved [2].

This study aimed to develop a core competency model for translational medicine curriculum in the Korean graduate education context. If we intend to develop a clear and valid model that is widely accepted within the Korean academy, a consensus should exist among the specialists and key stakeholders involved in the field of translational medicine research in Korea. This study invited specialists and key stakeholders to develop a consensus on a core competency model.

Methods

1. Working group

Seventeen specialists were invited to take part in the working group. Most of them were translational medicine specialists with medical background from the Department of Translational Medicine of a single medical college. Two other specialists who had both medical background and doctor of philosophy in education were from the Department of Medical Education at the same institution. Most of the members of the working group were also included in the survey group later.

2. Survey group

Translational medicine specialists and key stakeholders were invited to participate in the survey group to collect their ideas and arrive at a consensus on the core competencies of translational medicine research. Eighty specialists engaging in translational medicine research at a single medical college made up most of the survey group. Twenty-five other specialists and key stakeholders from different colleges, universities, and research institutions in Korea were also added to the list. They survey results were collected only from the participants who agreed with the purpose of the survey.

3. Process

First, the working group reviewed previous studies on core competencies and training programs for clinical and translational medicine research from global perspectives [3,5-7]. Then, the working group made an initial draft of the core competency model in English based on the literature review. The initial draft was sent to the survey group by email to ask whether they agreed or disagreed with each core competency. The survey group was also allowed to propose new competencies that were not listed on the initial draft. The email was sent 3 times or until a reply was received. Opinions on each domain of core competencies were also collected through the survey. After the survey, the working group simplified, merged, or excluded the competencies that received less than 80% agreement among the survey respondents. The working group also reorganized the order of the domains and competencies based on the survey results, and clustered the domains into four major areas. Finally, the working group made a list of specific competencies for each core competency that describe the core competencies in detail. The English version of the core competency model was translated into Korean by the working group.

Results

1. Initial draft and survey results

The initial draft had 13 domains and 46 core competencies. 41% (43 out of 105) of the survey group responded to the survey. Thirty-five specialists from a single medical college and eight specialists from other institutions responded to the survey on the initial draft (Table 1). Eighty percent (36 out of 46) of the initial core competencies received an agreement from above 80% of the survey group. The average rate of agreement with the competencies was 87%±10%. The survey respondents expressed several major opinions on the initial draft of the core competency model. First, they stated that there should be an order among the domains and competencies in the model. Many of them suggested that the domains should be aligned from the fundamental elements to the practical elements, and that the competencies in each domain should be aligned from early and basic competencies to late and more difficult competencies. Second, they pointed out that some of the competencies overlapped with each other, and could be combined. Third, they indicated that some of the competencies seemed to go beyond the scope of translational medicine research and were more related to highly specialized expertise in other specific fields.

2. Core competency model

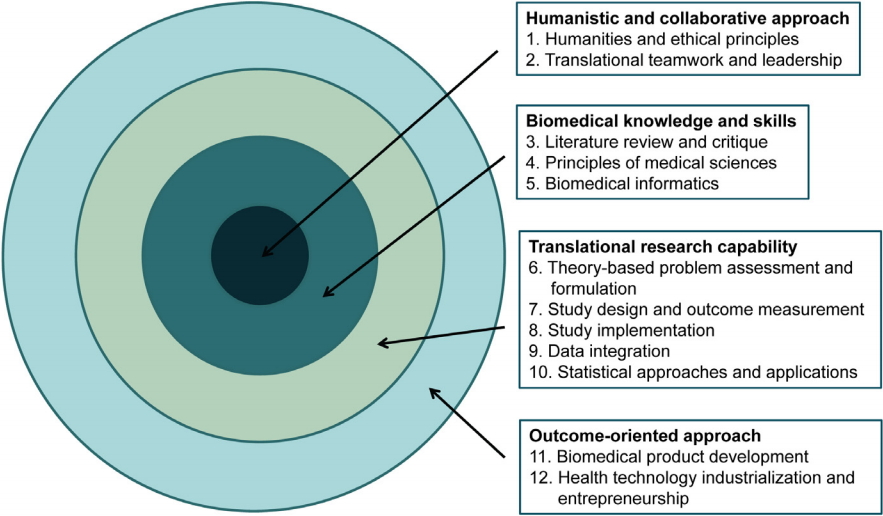

The final core competency model has four areas, 12 domains, and 34 core competencies (Table 2). The major areas, domains, and competencies are aligned from the innermost, fundamental elements to the outermost practical elements. The working group developed a round target figure to symbolize this model (Fig. 1). Each core competency has two to five specific competencies that describe the core competencies in detail (Appendix 1).

Discussion

Through this study, we were able to develop a core competency model for translational medicine curriculum in graduate education based on a consensus among the related specialists and key stakeholders in Korea. In most of the previous studies, the process to reach the consensus among the stakeholders was not clearly described [5,8]. This study adapted a two-step approach that was also used in a previous study, inviting the working group and a broader opinion group consecutively to reach a consensus [6].

The final core competency model has four areas, 12 domains, and 34 core competencies. Many of the domains and competencies in the Korean competency model are similar to those of other competency models in the literature. This may be due to the general concepts and common methodologies shared in biomedical research and the universal definition of translational medicine research worldwide [9]. However, there are also some differences between the Korean model and the other models. Our Korean model is structured in a more logical and systematic way. The domains are categorized into four major areas, and the major areas, domains, and competencies are aligned from the fundamental and basic elements to the practical elements. The Korean competency model also places a greater emphasis on the basic concepts and principles of medical science than other models. This may reflect the research environment in Korea, in which most translational medicine research is conducted by doctor of medicine scientists in medical institutions. Finally, there are two to five specific competencies for each core competency that describe the core competencies in detail, and the whole model is described in both English and Korean. This will help the Korean researchers and program directors understand and utilize this model.

Developing and evaluating competence within the translational medicine research field is not only important for educational needs, but also for the accountability of this field [9]. Core competencies for translational medicine research define the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to function successfully within this field [10,11]. Achieving competence is a developmental process that requires a gradual progression toward the integration of these knowledge, skills, and attitudes [12]. Competency-based education is a learning paradigm focused on what learners need to know and be able to do, based on the goals and objectives of the curriculum [13,14]. Thus, this new core competency model could provide guidance for the education and training of translational medicine researchers in Korea.

This study also has some limitations. We were not able to invite all the specialists and stakeholders involved in the field of translational medicine research in Korea. Most members of the working group were from a single institution, and the majority of the respondents to the survey were also from the same institution. Some of the members in the working group also participated in the survey. The last version of the core competency model was not sent to the survey group again for an eventual agreement. Thus, this core competency model should not be perceived as a final fixed version but rather as an initial version that could be revised and updated continuously. Moreover, any individual institution may adapt and modify this model according to its specific needs and circumstances.

We developed a core competency model for translational medicine curriculum in Korea through a consensus among the specialists and key stakeholders in the field. This core competency model will help the developers of translational research education and training programs to articulate specific program objectives, create an appropriate curriculum, and assess whether program objectives and competency requirements are met.

Acknowledgements

None.

Notes

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work: HBY, DJP, JSS, CA; data collection: HBY; data analysis and interpretation: HBY, DJP, JSS, CA; statistical analysis: HBY; drafting the article: HBY; critical revision of the article: DJP, JSS, CA; receiving grant: DJP; and final approval of the version to be published: all authors.