Introduction

As Japan’s birthrate declines, its population ages, and medical technology advances, patients’ needs and individual patients’ values regarding medical care are diversifying. Furthermore, patients have become fully aware of their rights and are beginning to demand an emphasis on safety and peace of mind, as well as high levels of quality in their care. This requires physicians to respect patients’ wishes and values and provide medical care with emphasis on quality of life [1,2].

Currently, physicians cannot think of “physician professionalism” on their own because they practice team medicine and patient-centered medicine. It is indispensable to consider “physician professionalism” from the society’s viewpoint and interaction with various professions engaged in medical treatment.

The Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Model Core Curriculum for Medical Education (revised 2016) lists professionalism, medical knowledge and problem-solving ability, practical skills and patient care, communication skills, practice of team-based healthcare, management of quality of care and patient safety, medical practice in society, scientific inquiry, and attitude for life-long and collaborative learning as the nine essential curricular elements [3].

Based on the current state of medicine and the “basic qualities and abilities as a physician” in the Model Core Curriculum for Medical Education, medical students are required to have both medical knowledge and skills (e.g., high communication skills and professionalism), as well as the ability to respond to the patients’ and society’s needs [3,4].

Recognizing the importance of professionalism education, we have been conducting professionalism education for medical students through nursing practice as an early clinical experience training from their first grade. Students’ attitudes and behaviors must be corrected to develop professionalism. In nursing practice, medical students are shadowed by nurses to learn and understand the importance of relations with others as medical students based on a sincere attitude, gain awareness of nursing practice and understand nursing care, and participate in practical trainings with explicit consideration of their approach as medical students.

To date, there has been scarce research on the attitudes, actual learning, and educational outcomes of medical students’ undergoing nursing practical training as a form of professionalism education. Accordingly, this study aims to clarify medical students’ attitudes and behaviors, and document their learning experience during nursing practical training. The future goal is to use these findings to further improve professionalism education of medical students in Japan.

Methods

1. Nursing practice training

Nursing practice training was conducted for medical students in the latter half of their first year as an early clinical experience training to promote professionalism education. The goals of this nursing practice training are as follows: (1) learn about actual nursing activities; (2) understand how nurses relate to patients in the medical field and what nursing assistance is; (3) understand what roles nurses play in the healthcare team; (4) experience actual medical treatment situations of patients; and (5) learn about interprofessional cooperation between physicians and nurses in team medical care. In the nursing practice training, a medical student provides nursing assistance to a patient through shadowing by a nurse to achieve five nursing training goals. The nursing practice training period was conducted for 2 days on October 21 and 23, 2019. The nursing practice training was held at Tokyo Medical University Hospital. A questionnaire survey was carried out on October 21–25, 2019 via the learning management system (LMS) of Tokyo Medical University.

2. Subjects and data collection

A questionnaire survey was conducted on October 21–25, 2019 using our university’s LMS among our first-year medical students after completing their nursing practical training to better understand the students’ learning process and experiences. The survey content was about the students’ learning of nursing based on the achievement goals of the practical training and the status of their approaches to the practical training. They were also asked to write freely about their impressions and findings of the practical training. After completing the practical training, the students’ attitudes to their ward placements were evaluated using practical training evaluation forms by shadow nurses (i.e., others’ evaluation) and by the students themselves (i.e., self-evaluation).

3. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics was performed for each questionnaire item. For free-text responses, descriptions were grouped by input data with similar content and meaning, and then analyzed qualitatively. Others’ evaluation and self-evaluation were analyzed quantitatively. The selfevaluations were classified into two groups, namely, high and low groups. The classification criterion was based on the median of the mean total self-evaluation scores. The relationships between self-evaluations and others’ evaluations were statistically analyzed. The “evaluation chart for others and self in practical training” consisted of the following items: “able to appropriately greet staff,” “maintains standards of personal appearance (including uniform, hair, and name tag),” “abides by outpatient and ward rules and appointed times,” “attends to patients with a polite manner,” “active learner,” and “can communicate appropriately with the healthcare staff and patients.” Participants evaluated each statement on a 6-point scale from “very good” to “very poor,” with each rating assigned a corresponding numerical value (“very good”: 5 points, “good”: 4 points, “acceptable”: 3 points, “improvement required”: 2 points, “poor: 1 point, “very poor”: 0 points).

4. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University (IRB approval number: T2019-0083; approval date: October 3, 2019). During the nursing practice orientation, our first-year medical students were provided with a written explanation of the study describing its content, objectives, and ethical considerations, as well as a verbal invitation. The students were informed that their survey results and selfevaluation and others’ evaluation would be anonymized and statistically analyzed. The students received a verbal explanation, with reference to the written explanation of the study, that collaboration was voluntary and that they could withdraw their consent without penalty. Their consent or refusal to collaborate would have no influence on their grades, and the data obtained would be used to answer the study objectives. Those who consented to participate were classified as research collaborators and requested to sign a consent form.

Results

Consent for research cooperation was obtained from 76 first-year medical students. The self-evaluation of the nursing practice training was conducted by the 76 first-year medical students, and the others’ evaluation was conducted by 76 shadow nurses (response rate=100%).

1. Relationship between two groups of selfvaluation and others’ evaluation (t-test)

A t-test was conducted for the high and low groups of self-evaluation and others’ evaluation (Table 1). Based on the median of the mean of the total self-evaluation scores, the self-evaluation was classified into two groups: high group and low group. Values higher than the median of the mean score were designated in the high group. Values lower than the median of the mean score were designated in the low group. On the first day of the nursing practice training, the average self-evaluation total score was 25.74 and the median was 26. There were 36 persons in the high group and 40 persons in the low group. On the second day of the nursing practice training, the average selfvaluation total score was 26.49 and the median was 28. There were 31 persons in the high group and 44 persons in the low group.

On the first day of the nursing practical training, there was a significant difference in “maintains standards of personal appearance (including uniform, hair, and name tag)” between the high and low groups. There was a significant difference in “attends to patients with a polite manner” between the high and low groups. On the second day, there was no significant difference in all the assessment items between the two groups.

2. Average score of self-evaluation and others’ evaluation for each practical training day

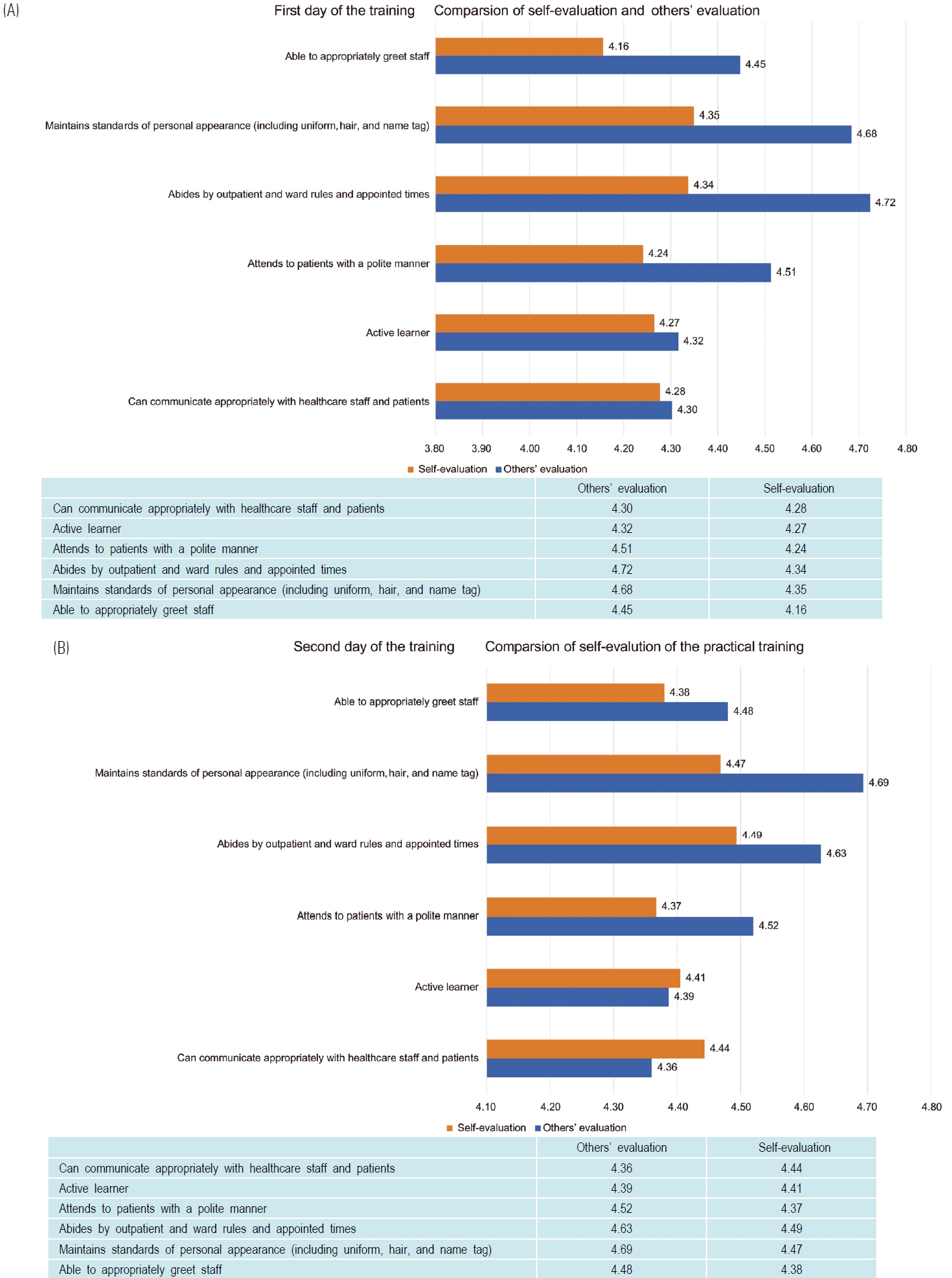

On the first day, all items had higher mean scores in the others’ evaluation than in the self-evaluation. There was a difference in the self-assessment and external assessment means for the statements “able to appropriately greet staff,” “maintains standards of personal appearance (including uniform, hair, and name tag),” and “abides by outpatient and ward rules and appointed times.” On the second day, the self-evaluation means for “active learner” and “can communicate appropriately with healthcare staff and patients” were higher than those for others’ evaluation. For “maintains standards of personal appearance (including uniform, hair, and name tag),” the “others’ evaluation” means were higher than the self-evaluation means by 0.22 (Fig. 1).

3. Questionnaire survey after nursing practice

After the practical training, a questionnaire survey was conducted for the participating students (Table 2). Fiftyive students responded to the questionnaire (response rate=72.3%). The students were asked to select one option in response to each of the questionnaire’s six statements. They described their impressions of and realizations from the training in a free-text response section (descriptions were requested). Most students (90%) responded that they learned what nursing work and care consist of, that they aimed to fulfill the training aims and engaged actively, and that they felt the training was complete. Descriptions with similar content and meanings were grouped by data and analyzed qualitatively. Eight categories were extracted (Table 3).

Discussion

1. Student attitudes as revealed by the evaluation of nursing practice

1) Relationship between the two groups of selfevaluation and each of the evaluation items of others’ evaluation

For the first day of training, others’ evaluation showed higher scores for the high self-evaluation group than for the low self-evaluation group for “maintains standards of personal appearance (including uniform, hair, and name tag)” and “attends to patients with a polite manner.” This suggests that students in the low self-evaluation group had not fully grasped the objectives of the practical training and therefore did not understand the attitude and approach with which to engage. This also suggests that students in the low self-evaluation group did not understand the significance and necessity of maintaining personal appearance and attending to patients with a polite manner.

For the second day of training, there were no differences in others’ evaluation between the high and low self-evaluation groups in all evaluation items. This indicates that by the end of day one and through their interactions with the shadow nurses, healthcare staff, and patients, students in the low self-evaluation group came to understand the objectives of the training, learned the right attitude, and know how to engage with their practical training. There was great awareness and learning with the shadow nurse after the practical training.

2) Comparison of mean scores between selfevaluation and others’ evaluation

For the first day of practice, all items had higher mean scores in the others’ evaluation than in the self-evaluation. This is because the evaluator gave a slightly lenient evaluation to a student who was new to hospital practice and had no knowledge of a medical specialty field, clinical practice, nursing care, or patients, although there were evaluation criteria. Itagawa et al. [5] stated that students’ self-evaluation fluctuates, is unstable, and tends to underestimate, which is unique to adolescents. In the present study, it was the first time for the students to do practical training in a hospital and hence their probable underestimation. For the second day of training, the average score of self-evaluation was higher than that of others’ evaluation for “active learner” and “can communicate appropriately with the healthcare staff and patients.” The average self-evaluation score was higher than the average others’ evaluation score because the students learned the necessity of communicating with the medical staff and patients and actively engage in practical training based on their first day of experience.

3) Attitude education in nursing practice

Okazaki et al. [6] described some inappropriate behaviors of medical students, including lack of basic learning attitude, lack of positivity and sense of purpose for practical training, and lack of communication. They stated the importance of feedback on these inappropriate behaviors. Papadakis et al. [7] and Yates [8] reported that students who had academic or behavioral problems while in medical school were at a greater risk of engaging in unprofessional behavior after becoming physicians. Thus, shadow nurses should review the performance of students after the practical nursing training, asking them about their efforts and attitude during the training. To foster professionalism, attitude education is very important because it enables medical students to correct their behaviors and attitudes through early appropriate guidance upon entering medical school. Ueno et al. [9] reported bad impressions of medical students in their patient escort practice training because of their inappropriate appearance and hairstyle, not listening to the medical staff or patients, being indifferent to patients, and not motivated to practice. In the present study, students who greeted others, were well groomed, and interacted with patients politely were rated highly in others’ evaluation. Thus, the four important basic elements of attitude education include greeting, appearance, ability to communicate with others, and willingness to engage in practical training. Nursing practice is also useful for attitude education of nonmedical people.

Ueno et al. [9] described attitude education as education that fosters a spirit and attitude of compassion toward others. This includes patients, those working in other disciplines, and healthcare staff. Such education encourages understanding of patients’ feelings and promotes empathy for patients. Such attitude should be shown in medical care by students when they become physicians. To acquire “basic qualities and abilities as a physician” as indicated in the Medical Education Model Core Curriculum, and to send out as many high-quality doctors with excellent character and human nature as possible globally, it is urgent to review and restructure the attitude education system to enable other specialists to participate in attitude education [3].

2. Learning and awareness in nursing practice

Students understood that nursing care involves daily life care of patients by nurses, and that nursing care supports the patients’ hospital stay and treatment. The understood roles of nurses include their closeness and the importance they give to patients; their collaboration, cooperation, and information-sharing with physicians; and their being an important member of the medical care team. The students understood that patients are admitted to the hospital and receive assistance from nurses regarding their personal matters while suffering and anxious about their treatment and medical conditions. The students understood that the patients had various restrictions on their activities because of their medical conditions, and that only a curtain separates them from other patients making it difficult to protect their privacy. Regarding multidisciplinary collaboration, the students realized the importance of different specialties in terms of sharing information and utilizing their respective specialties for the treatment and recovery of patients. Clear communication was understood to be crucial for effective collaboration between doctors and nurses, multidisciplinary collaboration, and patient interaction. These aspects were learned by the students from seeing and experiencing the actual work of nurses and how they care for patients through shadowing by nurses and inter-medical conferences with nurses.

Sakurai et al. [10] stated that nursing practice is an excellent opportunity for medical students to learn more about the actual work of nurses who interact closely with doctors, and the nature of patient-centered medical care. Emori et al. [11] stated that “medical students who experienced nursing practice had a deeper understanding and a positive view of nursing and nurses. Thus, the students’ understanding and learning were acquired from their experiences and observations of the nursing practice. The students’ awareness areas include “what is required of physicians” and “what was good about the practical training.” these contents are interrelated and are characteristic of student learning in this study.

Regarding “what was good about the practical training,” the students shared “I was able to see doctors from a nurse’s point of view,” “I was able to observe other approaches to handling patients,” and “I learned about the responsibilities of doctors from the perspective of nurses.” Thus, the students had the opportunity to see the position of a physician objectively through their nursing practice. A student response stating, “I witnessed occasions when doctors spoke harshly toward nurses or showed bad attitudes, and learned the importance of respecting the people you work with.” This observation of the bad attitude and behavior of physicians provides students with a vital lesson in “what is required of physicians” in terms of how physicians should conduct themselves.

Helmich et al. [12] reported that medical students learned how to show empathy toward patients and respectfully collaborate with nurses and other healthcare professionals as future physicians by participating in nursing practice during their first year. Jain et al. [13] found that 75% of medical students had increased respect for nurses’ knowledge and skills after undergoing a nurse shadowing program for first year medical students and learning about nursing and nurses’ roles. The medical students showed improved attitude toward nurses and in acquiring knowledge. They stated that nurse shadowing programs provide a foundation for medical students to develop team medicine and multidisciplinary attitudes.

The present study consisted of self-evaluation and others’ evaluation after the completion of a nursing practice training. Previous studies have not conducted self-evaluation and others’ evaluation [6,9,10,11,13]. Medical students evaluated the content of their own nursing practical training (self-evaluation). Through this evaluation, they (1) reflected on how they had conducted their own nursing practice training, (2) objectively viewed their own learning, and (3) clarified issues regarding the next day’s practice training so that they could achieve their goals for the nursing practice training. In the present study, nurses who shadowed medical students evaluated the medical students. Their assessment constituted others’ evaluation. These nurses evaluated whether the medical students were able to acquire the basic attitudes and demeanor as a future doctor. Based on this others’ evaluation, the nurses advised the medical students based on their individuality and guided them to achieve their nursing practice training goals. The others’ evaluation by the nurses facilitated the achievement of goals of the medical students in their nursing practice goals training. By receiving individualized guidance from the nurses and through self-evaluation, the medical students learned the basic attitudes and demeanor of a medical professional, what is expected of doctors, the lives of hospitalized patients, nursing care, and multidisciplinary collaboration. We observed and felt that the medical students have grown more through this learning process. In addition, the comparison of self-evaluations with others’ evaluations also revealed differences in the perceptions between the nurses and the medical students. These results will serve as vital preliminary data for improving nursing practice training for medical students in the Japanese setting in the future. These are the important differences between the previous studies and the present study.

In the present study, the practical training increased the medical students’ awareness of the importance of preparation in becoming physicians. The students had the opportunity to consider how they should learn vital lessons and develop themselves as future physicians.

Through the nursing practical training, the medical students could deepen their understanding of clinical practice and hospitalized patients, and internalize what is required of physicians. The students were able to get a sense of what it is like to be a doctor from the viewpoint of nursing practice, look at their position as a doctor objectively, and imagine their future role as a doctor. They became more cognizant of their responsibility as doctors to protect human life and health. Nursing practice is thus an excellent training for attitude education during the first year of medicine.

3. Issues for further study

Some opinions on the practical training in the questionnaire survey included, “it is not necessary to do nursing practical training because you will become a doctor” and “practical training is boring. Therefore, it is necessary to review and revise the practice orientation and nursing practice so that students can fully understand the purpose and goals of nursing practice and engage in practical training.” Thus, there must be a practical training orientation (e.g., lectures about nursing) to teach students about nursing and patients before attending the practical training. By following the guidance of shadowing nurses and carrying out procedures learned in class (e.g., measurement of vital signs and communicating with patients) under nurse supervision, medical students are able to appreciate the value of practical training in preparing them as future physicians and in changing their perception that practical training is boring.

4. Limitations of the study

There is a limitation in generalizing all the study findings as the opinions of ward nurses regarding the practical training were not fully clarified. In the future, it is necessary to incorporate all the suggestions obtained in this study and further accumulate data through repeated studies to allow generalization.